A Retrospective Bruce Gilden's 50 Years of Capturing Raw Humans.

By Ellis C. Vesper

Dec 10, 2024

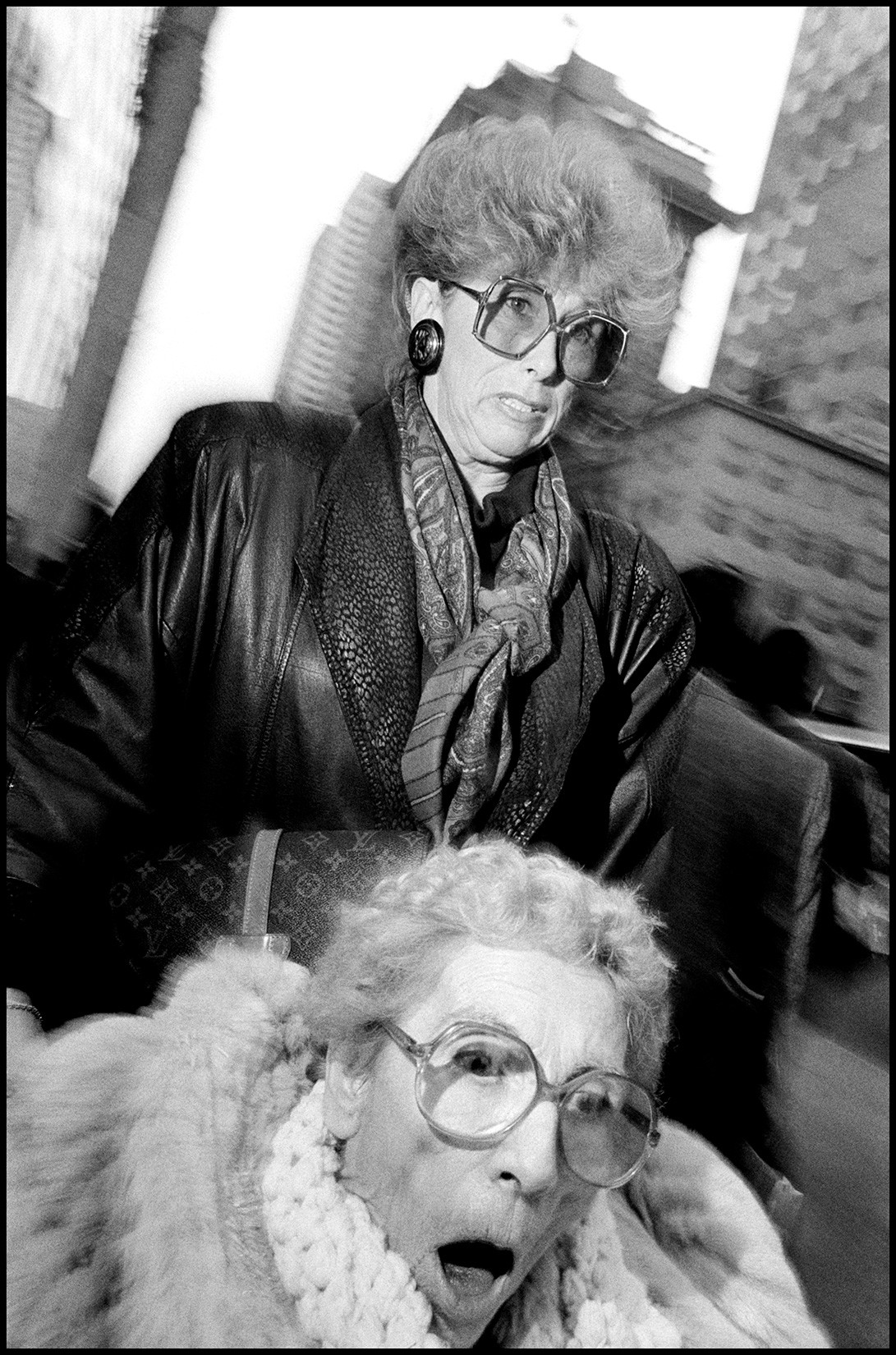

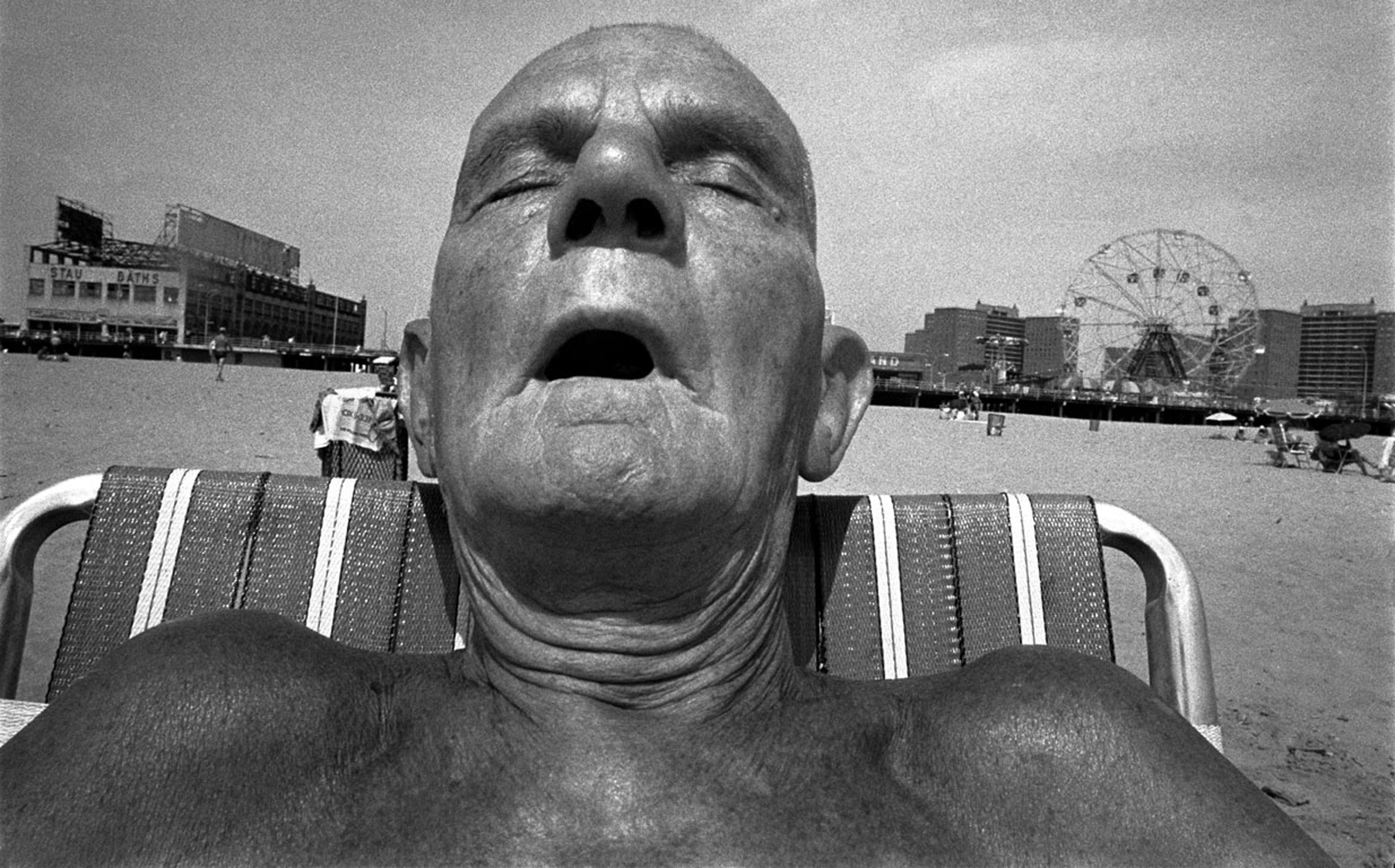

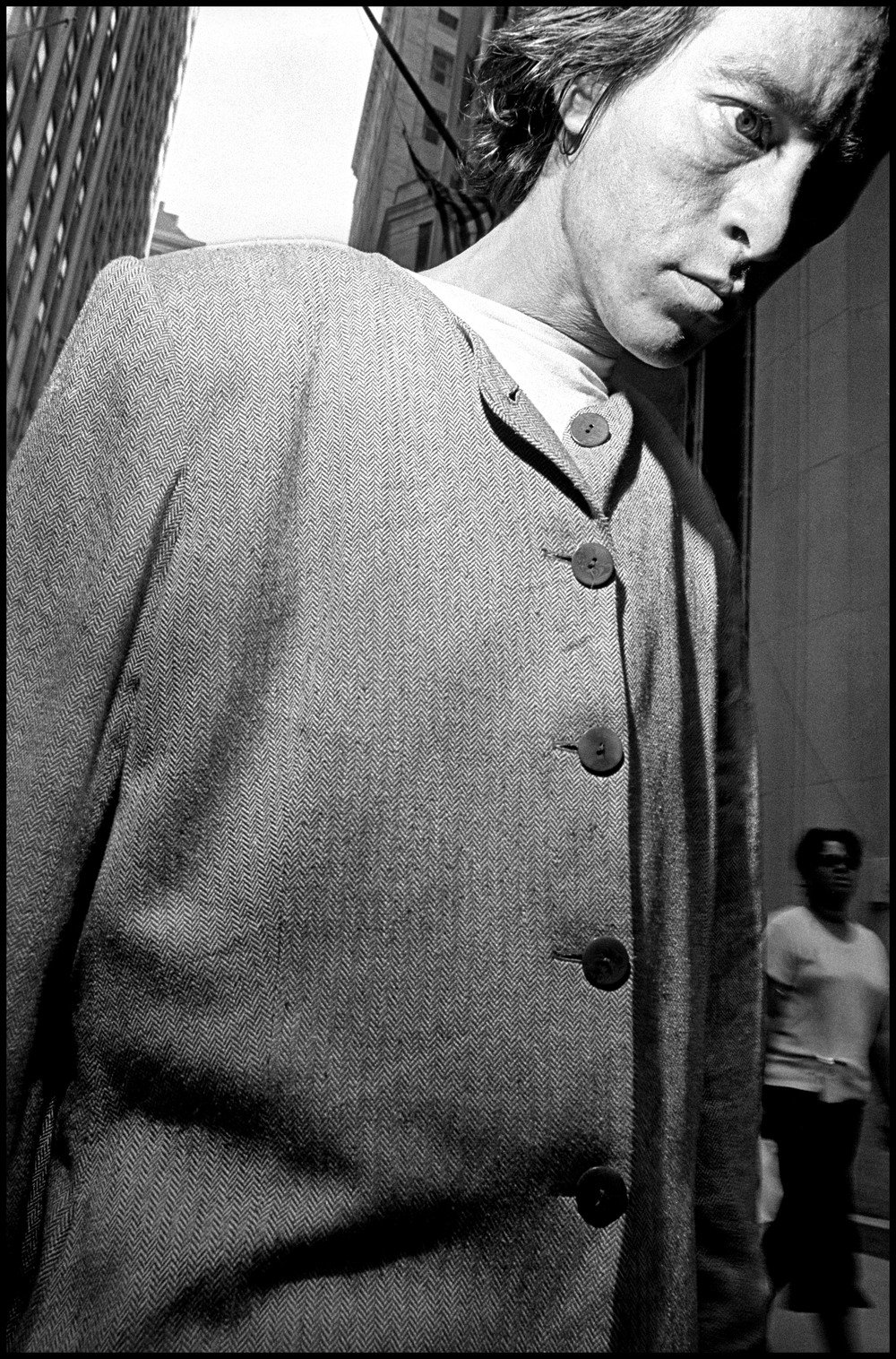

The Met has a collection of assault photography hanging on its walls. That's what Bruce Gilden's work technically is; he attacks strangers with a Leica and a flash powerful enough to give anyone a seizure, stealing frames of their daily lives without warning or apology. For half a century now, this lunatic has turned Manhattan's sidewalks into his private hunting ground and somehow ended up being called a genius.

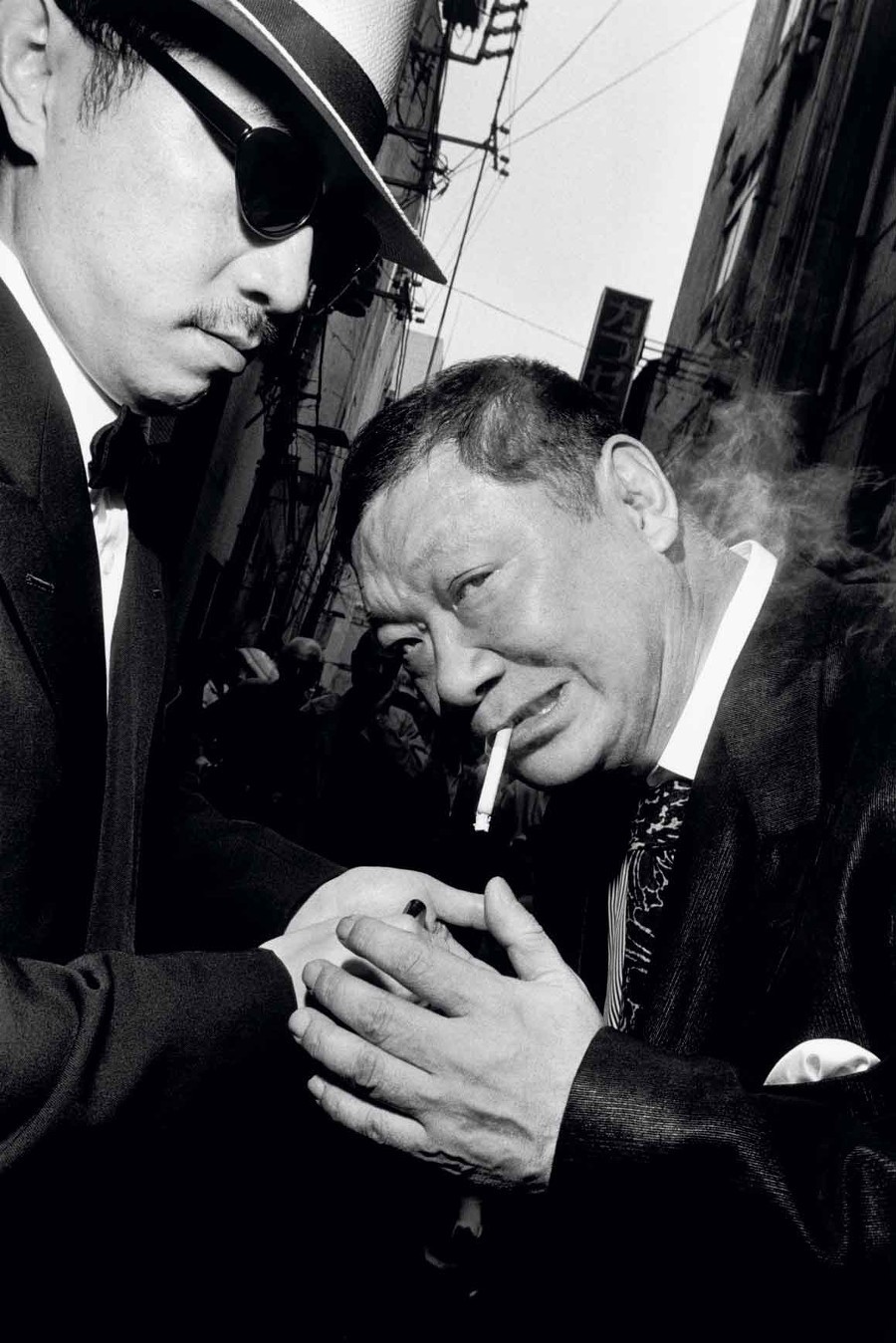

His photographs document raw humanity. Faces between shock and rage, every pore and wrinkle blasted into stark relief by his flash. No posed smiles, no careful compositions, pure fight-or-flight response seared onto the film. Each frame captures an informal and unauthorized autobiography in 1/125th of a second. While technically legal in American public spaces, his approach courts controversy and occasional violence. European privacy laws would make his style practically criminal. Yet he keeps shooting, decades after most photographers would have been slapped into retirement.

Gilden learned photography by shooting Coney Island mobsters in the 1960s. His dad, a small-time gangster himself, inadvertently prepared him for a career of confrontation. "Growing up, there was always tension in my house," he recalls. "Maybe that's why I'm comfortable with conflict. When you've lived with it your whole life, what's one more angry person?”. Kind of makes you feel for the guy.

The streets schooled him some more. Manhattan in the 70s and 80s bred a particular brand of crazy. Gilden's technique evolved in those wild streets, getting close, shooting fast, and dealing with consequences later. He worked exclusively with wide-angle lenses, forcing himself to get the lens right up in people’s faces, freezing that microsecond when masks slip, and raw humanity emerges.

"I'm known for taking pictures very close, and the older I get, the closer I get," Gilden explains in his thick Brooklyn accent. "If you're going to take a picture of someone, you might as well come in close. Otherwise, what's the fucking point?"

His success spawned legions of imitators, of course. The rise of digital cameras created an army of Gilden-style shooters, each trying to out-assault the master. The result is most likely a restraining order instead of gallery shows. Or, best case scenario, a photo taken from too far away to even look remotely similar. Notable exceptions are Daniel Arnold, and, more recently, Trevor Wisecup, as for the rest. They've got the flash but not the purpose, only the aggression without the vision. Street photography forums overflow with discussions about model releases and legal risks, concerns Gilden bulldozed through by simply not giving a fuck.

There’s even a video on Youtube of a guy setting up a mannequin in his living room to practice getting up close, now, I don’t mean to hate, but if there’s one thing you do need for shooting Gilden style, its the fuck you attitude, forget the mannequin and get out there. Or just take some nice pictures of a dressed-up mannequin in your living room, which frankly sounds more interesting than a half-assed Bruce Gilden attempt.

The fashion world, desperately chasing authenticity, eventually came knocking. They hired him to bring his "aesthetic" to commercial shoots, demanding a sanitized version of his street rawness. The results feel a bit hollow, to be honest, permission strips the power from his approach. Without the stealing, the moment feels like just another well-lit fashion shoot. But I get it, a man’s gotta eat.

Even Magnum Photos, that bastion of photographic respectability, had to acknowledge his impact. They made him a member, legitimizing his work. But institutional acceptance can't soften what makes his work powerful: the raw violation of social norms.

His recent work is quite different, but in the same vein of extreme close-ups of society's overlooked, now forcing us, the viewers, to have a confrontation with faces we train ourselves to avoid, like addicts, homeless folks, prostitutes, etcetera. No comfort, just stark reality at point-blank range.

This brutal approach gains new relevance in our current privacy paradox. We freely surrender our data to Zuck while becoming increasingly protective of our own public image. Social media platforms harvest every detail of our lives, but we panic at the thought of an unflattering candid photo. Surveillance cameras track our every move, but we demand control over how we're portrayed.

Gilden's flash cuts through this hypocrisy. His subjects get no chance to curate their image, filter their flaws, or control their narrative. They exist in his frames exactly as they were in that startled moment, genuine and unfiltered. This violation feels almost like an elevation at times.

The art world can debate the ethics of his work. Street photographers can argue about model releases and privacy rights or how to be sneaky in public. Social critics can dissect the power dynamics of his approach. But Gilden just keeps shooting, creating unauthorized portraits of humanity one flash at a time. His work survives because it captures something essential about being human, even if he has to blind you to get it.

His photographs hang in museums now, evidence of a way of seeing that might not be possible much longer. As public space becomes increasingly regulated, as privacy laws tighten, and as everyone becomes more protective of their image, Gilden's brand of photography edges toward extinction. Each frame preserves the startled face of everyday humans, and a moment when art could still prioritize truth over permission.

Just duck if you see him coming. He doesn't need your consent to make you immortal. Let him hang your face up at the MET. It’ll make for a neat conversation starter.