How Communist Yugoslavians Went Hard Into Mexican Music.

By Rodrigo Garza

Dec 19, 2024

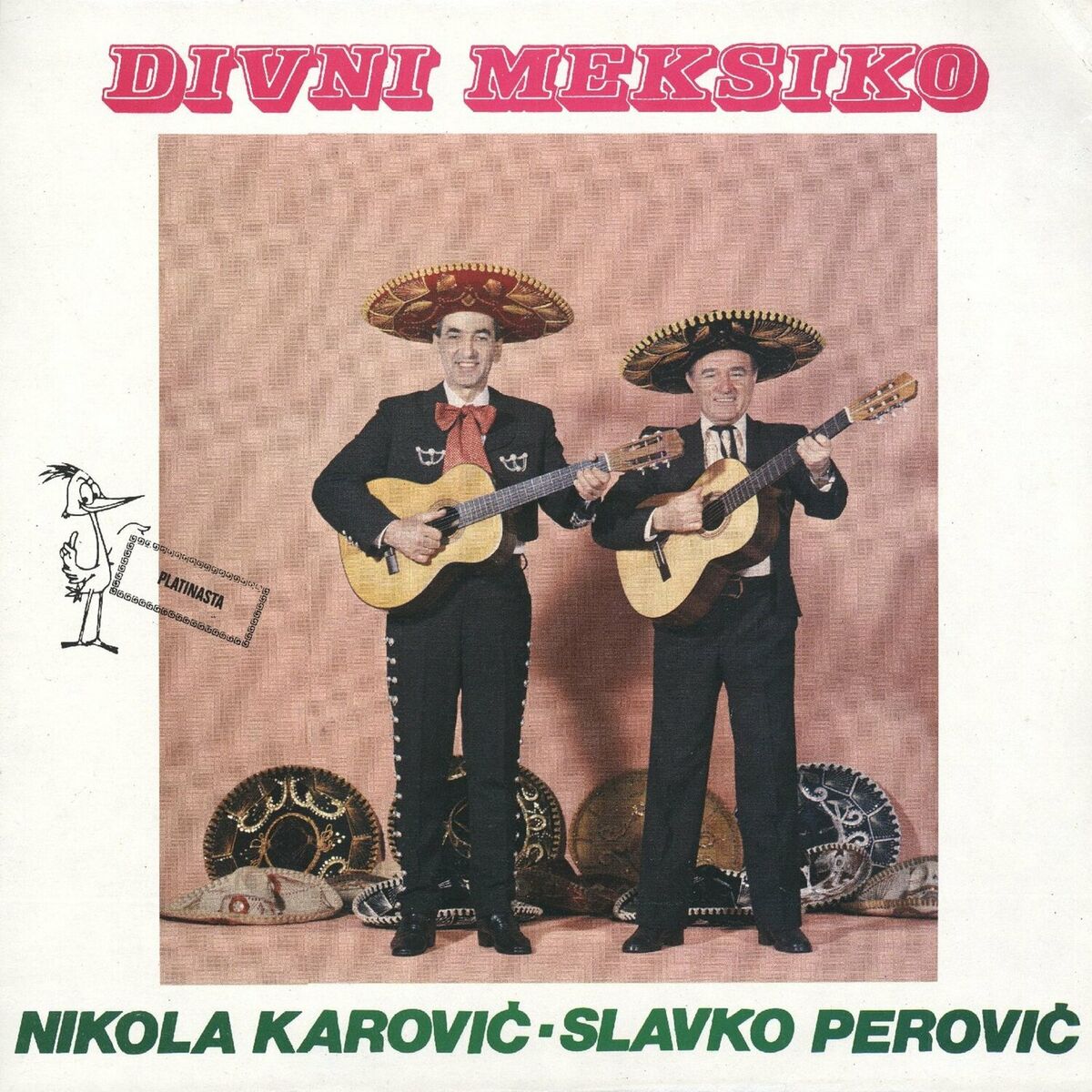

In 1956, while Elvis scandalized American television, Yugoslav musician Nikola Karović donned a sombrero and sang "El Rancho Grande" in heavily accented Spanish to thunderous applause in Belgrade. That moment marked the peak of Yu-Mex, Yugoslavia's bold cultural gambit in the Cold War's diplomatic wilderness.

The Yu-Mex phenomenon bloomed in 1948 after Tito's split with Stalin. While Western Europe embraced American rock and roll and the Eastern Bloc celebrated Soviet-approved folk music, Yugoslavia forged a third path through Mexican boleros and rancheras. Mexican culture solved Yugoslavia's entertainment crisis without entangling the country in Cold War politics, while its revolutionary aesthetic bolstered Yugoslavia's carefully cultivated image of independence.

Mexican films arrived first, flooding Yugoslav theaters with tales of passion and revolution. Post-war Yugoslavia craved narratives divorced from European conflicts yet resonant with its partisan spirit. The Golden Age of Mexican cinema delivered, particularly through its musical numbers. Local musicians rushed to meet the sudden demand for this new sound, creating something unprecedented in the process.

Slavko Perović sold over a million records in a country of 16 million people, transforming Mexican music into a distinctly Yugoslav art form. His performances merged charro suits with Balkan sensibilities. Through Spanish lyrics and Mexican arrangements, he gave voice to emotions that post-war Yugoslav society struggled to express directly. Each concert became a cathartic ritual, with audiences processing their own experiences through this exotic musical lens.

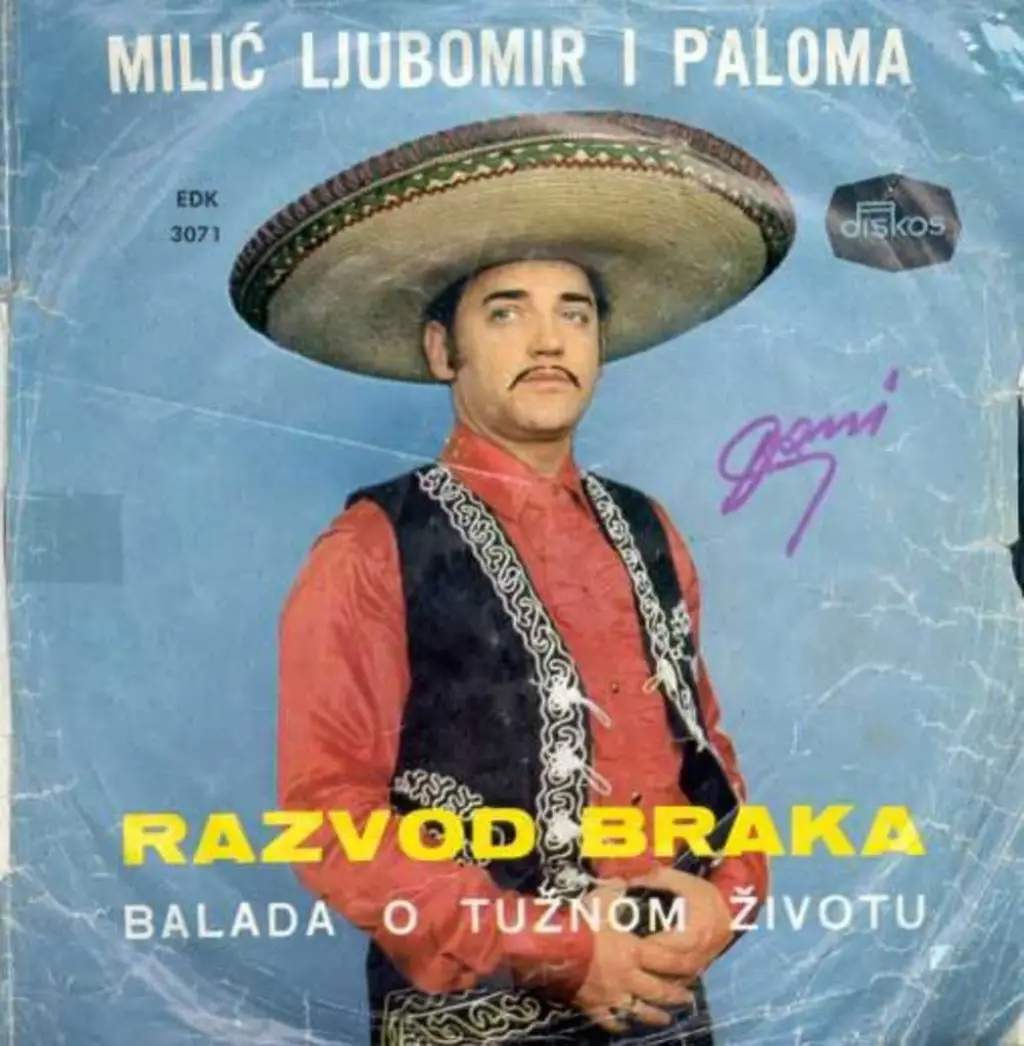

The technical achievements of Yu-Mex musicians deserve serious examination. Yugoslav accordionists adapted mariachi rhythms to Balkan dance forms, incorporating asymmetrical time signatures characteristic of local folk traditions. Ana Milosavljević brought microtonal Balkan vocal techniques to rancheras. Trio Paloma developed complex arrangements merging mariachi brass with Yugoslav folk harmonies. These innovations required deep understanding of both musical traditions, resulting in recordings that captured a singular moment in musical evolution.

Belgrade and Zagreb studios became sonic laboratories. Engineers developed new techniques to capture this hybrid sound, creating a distinctive production style that defined the genre. The raw energy of these recordings still startles modern listeners, preserving the urgency of cultural innovation under pressure. Each surviving vinyl tells the story of musicians and technicians pushing the boundaries of their equipment and expertise.

The visual aesthetic of Yu-Mex emerged through careful cultivation. Performers developed stage wear that merged Mexican and Balkan elements down to the embroidery patterns on their jackets. Album covers and concert posters from the era document this visual fusion. The photography archives of major Yugoslav cultural institutions reveal how these performers crafted their images with remarkable precision, creating a visual language that spoke to both traditions while remaining distinctly Yugoslav.

Yu-Mex spawned its own cultural ecosystem. Fan clubs published newsletters featuring Spanish language lessons alongside artist profiles. Performers toured smaller cities with combination concert-lecture programs, explaining Mexican cultural traditions to eager audiences. Radio DJs became cultural interpreters, providing context alongside the music. The movement penetrated Yugoslav society far beyond mere entertainment.

The phenomenon sparked broader cultural changes. Fashion designers incorporated Mexican motifs into ready-to-wear collections. Restaurants experimented with Yugoslav interpretations of Mexican cuisine. Dance schools taught modified versions of Mexican folk dances adapted to local social customs. Yu-Mex became a lens through which Yugoslavia explored its own creative possibilities.

By the 1970s, as Yugoslavia opened to Western influence, Yu-Mex evolved beyond its original purpose. The genre's emphasis on emotional directness influenced Yugoslav popular music for decades. Its technical innovations in arrangement and recording shaped studio practices well into the 1980s. The movement's impact extended far beyond its active years.

Contemporary scholarship reveals Yu-Mex's significance as more than a cultural curiosity. Dr. Miha Mazzini's research demonstrates how the movement exemplified cultural adaptation under political pressure. The genre challenged conventional notions of cultural influence, showing how societies transform borrowed elements according to their own needs.

Modern artists sampling Yu-Mex recordings often miss the crucial historical context. The genre emerged from specific pressures, providing Yugoslav society with tools for artistic expression during intense isolation. Its success stemmed from its ability to address cultural needs while maintaining political independence.

The Yu-Mex archive - recordings, photographs, and documents - preserves a moment of remarkable creativity under constraint. These artifacts challenge assumptions about cultural influence and adaptation. While global culture now flows through official channels, Yu-Mex demonstrates how the most innovative artistic developments often emerge from necessity.

Each surviving Yu-Mex recording captures a society transforming borrowed forms into something uniquely their own. In our era of instant global access to culture, such distinctive regional mutations become increasingly rare. The Yu-Mex phenomenon reminds us that true cultural innovation often requires resistance, constraint, and the courage to forge unexpected connections.