Europe’s city centers have become sanitized tourist traps. From rubber ducks in Amsterdam to Ridiculous close-ups of your eyes in Paris, is authenticity lost forever?

By Lightyears Team

Sep 10, 2024

There was a time when travel was all about discovery. You’d step off a plane in a new city, eager to lose yourself in the winding streets, to soak in the essence of the place, to engage with its culture, food, and people. Today, though, those moments of discovery feel like a distant memory. The European city center has become a global stage—an open-air theme park for tourists—designed not for exploration but for consumption.

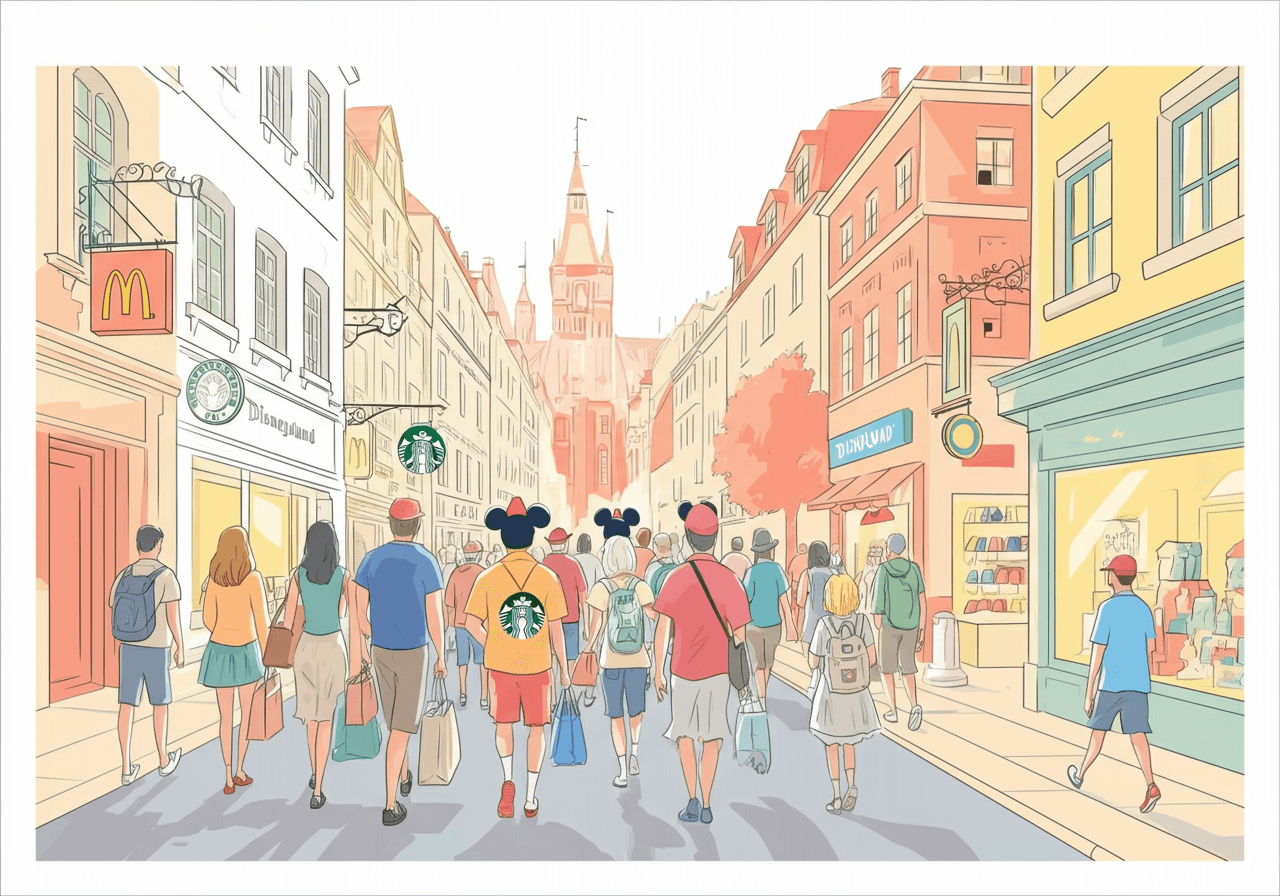

In places like Amsterdam, Paris, or Prague, it’s hard to shake the feeling that you’ve stumbled into the Disneyland of Europe, where authenticity has been replaced by shallow commercialism. Since when does someone visiting Amsterdam’s canals for the first time give any fucks about rubber ducks? Every corner shop seems to sell the same meaningless trinkets—miniature clogs, tulips, more rubber ducks—cheap, consumable artifacts that have more to do with turning a quick profit than with the city’s actual history or culture.

Disneyfication: When Cities Become Brands

The Disneyfication of European cities isn’t a mere nuisance. It’s a symptom of a deeper problem. All across the continent, cities are being stripped of their authenticity, turning into something that feels more like a brand than a place with real history and culture. Prague, for instance, has become a haven for tourists looking for the next big Instagram photo op, with endless trdelník pastries stands popping up on every corner, these diabetes fleshlight aren’t even traditionally Czech—it’s a shallow, tourist-friendly product designed for mass appeal.

And it’s not just the food that’s becoming generic. SIM card vendors and chain restaurants like McDonald's and Burger King are taking over historic spaces, filling in where authentic, local businesses once thrived. Why is it easier to find a Big Mac in the heart of Prague than it is to find a traditional Czech restaurant? Because cities are no longer catering to their locals—they’re catering to tourists who want something familiar and easy, not something that challenges them to experience the place they’ve come to visit.

The Global Homogenization of Europe’s Cities

The same story is playing out across Europe. Paris, one of the world’s most iconic cities, is being overrun by tacky tourist shops. Try walking down the streets of Montmartre without running into one of the 13 goddamned Iris galleries (real numbers). Who’s even buying this crap? And it gets worse. In the Netherlands, Argentinian steakhouses are crowding out local dining options. If you’re in Amsterdam and tempted to eat in one, here’s a better idea: starve instead.

The transformation of these cities is more than just an aesthetic tragedy—it’s a cultural one. When cities become cookie-cutter versions of themselves, designed for easy consumption, they lose the very essence of what makes them special. What you’re left with is a sanitized, commercialized version of a place, an Instagrammable backdrop where real life once existed. Looking more like an American city less than 100 years old, rather than 1000 year old wonders.

Cultural Colonialism: The Hollowing Out of Local Identity

What we’re witnessing is a form of cultural colonialism, where the unique aspects of a city are stripped away and repackaged for tourists. The architecture (parts at least) remains, but everything else feels like it’s been put on display, like a real-life version of a museum exhibit that people can walk through, snap some photos of, and leave without ever engaging with. In places like Venice, this process is particularly stark.

Once the crown jewel of Europe’s maritime empire, Venice now faces an influx of over 30 million tourists annually, many of them from cruise ships that dump thousands of people into the city for just a few hours. These tourists don’t stay long enough to engage with the city, they don’t support local businesses, and they certainly don’t care about Venice’s history. They come, they consume, and they leave, often leaving behind more damage than revenue. This mass influx has caused so much strain that Venice has begun banning large cruise ships from entering its fragile canals, a move that’s long overdue.

But even with these efforts, the damage is already done. Venice is becoming a shell of itself, with locals pushed out and replaced by a steady stream of tourists whose presence turns the city into a living theme park. The city’s population has dropped dramatically from 174,000 in the 1950s to around 52,000 today. Those who remain are often forced to live far from the tourist-heavy center, leaving Venice’s streets almost devoid of real residents.

Tourism’s Hidden Costs: The Loss of Authenticity

This transformation is happening everywhere. In Lisbon, neighborhoods like Alfama and Bairro Alto have been overtaken by Airbnb rentals, driving up housing prices and forcing locals out. What was once a tight-knit community is now a rotating cast of tourists, staying for a weekend and leaving behind nothing but noise and trash. The same phenomenon is occurring in cities like Barcelona, where anti-tourism protests have erupted in recent years as residents fight to reclaim their homes from the forces of mass tourism, reaching the extremes of locals shooting tourists with water guns while they dine in tourist trap restaurants in La Rambla.

The rise of short-term rentals is one of the biggest drivers of this transformation. In many cities, more than 20% of homes in the most popular areas have been converted into short-term tourist accommodations. While this is great for visitors looking for an authentic experience, it’s disastrous for locals who can no longer afford to live in their own neighborhoods. The result is a city that feels more like a hotel than a place where people actually live. And the authenticity of the homes is debatable, since you’re more likely to encounter a flat made to cater short term rentals than a true local flat. With the most basic less than minimalist furnishings the owners bought in bulk for their managed properties.

The food, too, has become part of this process of commodification. Instead of being challenged to try something local and unfamiliar, tourists are served watered-down versions of traditional dishes, made to appeal to the global palate. And when every restaurant starts to serve the same bland, tourist-friendly menu, the real flavors of a place are lost forever.

Who’s Really to Blame?

It’s easy to blame the tourists for this mess. They’re the ones crowding the streets, snapping selfies at every monument, and lining up for overpriced ice cream. But the truth is more complicated. Tourists are just a symptom of a much larger problem. The real issue is a system that prioritizes profits over culture, a system that has turned tourism into a global industry focused more on numbers than on quality. Governments, corporations, and local authorities have sold out their cities, allowing them to be transformed into tourist playgrounds where culture is commodified and authenticity is sacrificed for convenience.

In places like Matera, Italy, which was named the European Capital of Culture in 2019, tourism has skyrocketed, bringing with it all the trappings of mass tourism—overpriced hotels, tourist traps, and a growing sense of cultural erosion. Even programs like this, which are meant to highlight local culture, often end up turning cities into the very thing they were trying to avoid: shallow destinations designed for mass appeal.

Fighting Back: Overtourism Controls and Local Resistance

Not all cities are going down without a fight. Amsterdam, Venice, and Hallstatt in Austria have implemented bold measures to push back against overtourism. In Amsterdam, city officials have banned new tourist shops from opening in the city center and introduced a tourist tax to curb the flood of day-trippers. In Venice, the situation has become so dire that the city has begun charging tourists to visit, with plans to limit the number of visitors in the near future.

Hallstatt, a small town in Austria, has also taken radical steps to control the impact of tourism, implementing strict limits on the number of tourists allowed to visit each day. These measures, though controversial, represent a growing recognition that cities cannot survive under the weight of mass tourism.

The Future of European Cities: Reclaiming Authenticity

As Europe reopens post-pandemic, tourism is roaring back. And with it comes a sense of urgency—cities like Amsterdam and Venice can’t afford to go back to the old model of unchecked growth. The question is: Will cities learn from the pandemic pause and prioritize sustainable tourism moving forward, or will they double down on commodification, sacrificing their cultural heritage for short-term gains?

For tourists, the answer lies in making better choices. Skip the rubber ducks, the Instagram museums, and the Big Macs. Seek out what’s real—visit the places where locals still gather, eat food that hasn’t been diluted for mass consumption, and slow down enough to actually experience the place you’re in. Because if we keep treating Europe’s cities like Disneyland, they’ll soon become nothing more than hollow shells.

We don’t ant to tell you how to live your life and how to travel, but It’s time for a new era of tourism—one that values quality over quantity, experience over convenience, and authenticity over commodification, and above all, respect for the place.

Sources:

Hernández-Martín, R., & Schiemann, J. (2024). "Focusing at the Very Local Scale to Measure, Understand, and Manage Overtourism."

Vegheș, C. (2023). "The TESS of Cultural Tourism: The Digital Dimension."

Fragoso, M., Gonçalves, A., & Brito-Henriques, E. (2023). "European Capitals of Culture and Tourism: Place Branding and Beyond."

Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Russo, A.P. (2024). "Anti-Tourism Activism and the Inconvenient Truths