How Lee Miller’s journey from muse to war photographer redefined history and gave us one of WWII’s most iconic images.

By Rodrigo Garza

Dec 3, 2024

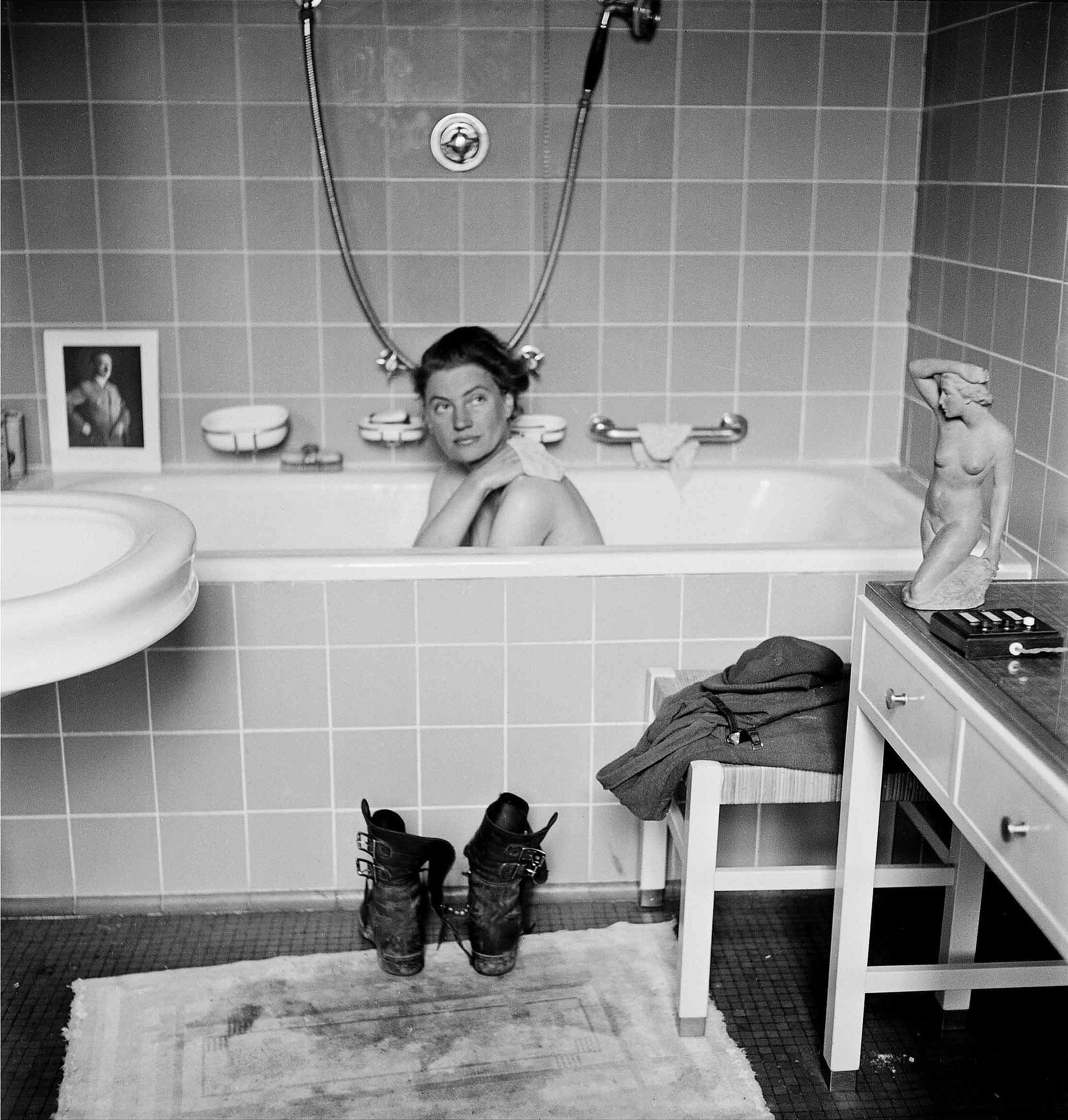

Lee Miller’s name is one that should stand among the greats of the 20th century. She was a woman who defied convention at every turn and left behind a legacy as provocative and complex as the images she captured. Among her most famous works, although as a subject, not the photographer, is the photo of her in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub, taken in his Munich apartment on April 30, 1945. This striking image, etched into our brains, is a symbol of defiance, irony, and the grotesque absurdity of war. With a forthcoming biographical film starring Kate Winslet set to explore her life, Lee Miller’s extraordinary journey finally poised to receive the recognition it has long deserved.

To fully appreciate the significance of the Hitler bathtub photograph, you have to understand the context in which it was taken. By the spring of 1945, the world was witnessing the collapse of Nazi Germany. Miller, then working as a photojournalist for Vogue, had been covering the war alongside her colleague and lover, David E. Scherman, who was a photographer for LIFE magazine. After documenting the liberation of Dachau, the pair traveled to Munich, where they gained access to Hitler’s private apartment. It was a surreal twist of fate: here was Miller, an American woman and a staunch anti-fascist, stepping into the dictator’s personal space and making it hers. The image of her reclining in his bathtub, her muddy boots slopped on the bathmat, is as visceral today as it was then.

In many ways, the photograph serves as a diorama of Miller’s approach to life and art. Her career had always been marked by a refusal to conform to traditional roles or expectations. Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1907, Miller’s early life was shaped by tragedy and resilience. but after being discovered by Condé Nast as a teen, she quickly rose to prominence as a model, gracing the pages of Vogue. But posing in front of the camera was not enough for Miller. She yearned to create, to be the one holding the lens.

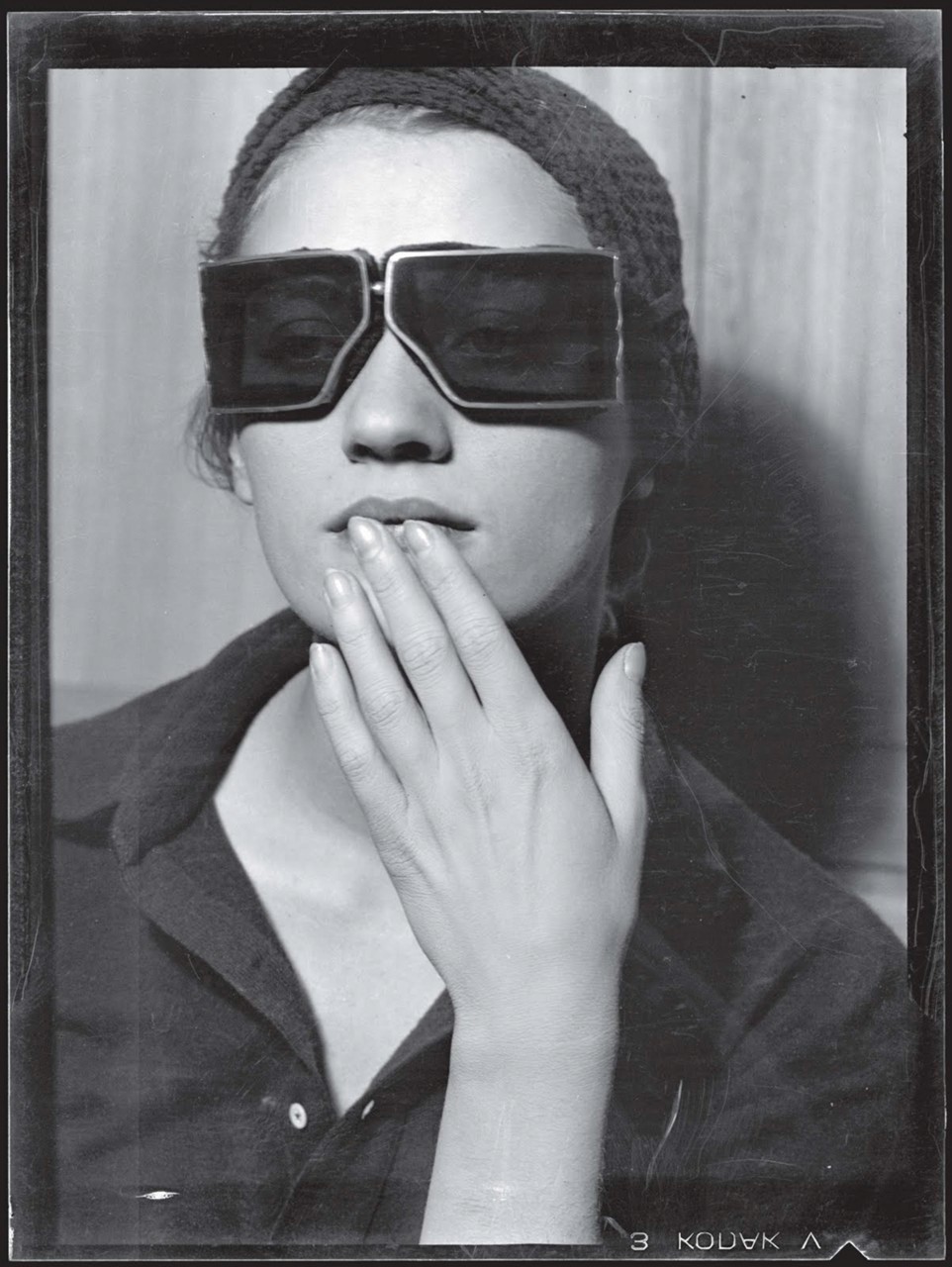

Her move to Paris in the late 1920s marked the beginning of her artistic transformation. There, she became the muse and lover of Man Ray, the great surrealist. Their relationship was romantic and professional, with Miller serving as his assistant and collaborator. It was during this period that she developed her own photographic style, characterized by its surrealist influences and technical precision. But, even as she thrived creatively, she struggled to be seen as more than Man Ray’s muse. The fact that some of their collaborative works were later attributed solely to him is a testament to the gendered biases of the art world.

Miller left Paris in the early 1930s, and this marked a new phase in her life. Returning to New York, she opened her own studio and began to establish herself as a photographer in her own right. Her portraits and fashion photography demonstrated a keen eye for composition and an ability to capture her subjects’ humanity. However, it was the outbreak of World War II that would really define her career. Moving to London in 1939, she found herself drawn to the chaos and devastation of the Blitz in London. Her photographs from this period, published in Vogue, are amazing for their emotional depth. They depict the destruction and also the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable hardship. and to be honest, seen from today, they feel surreal.

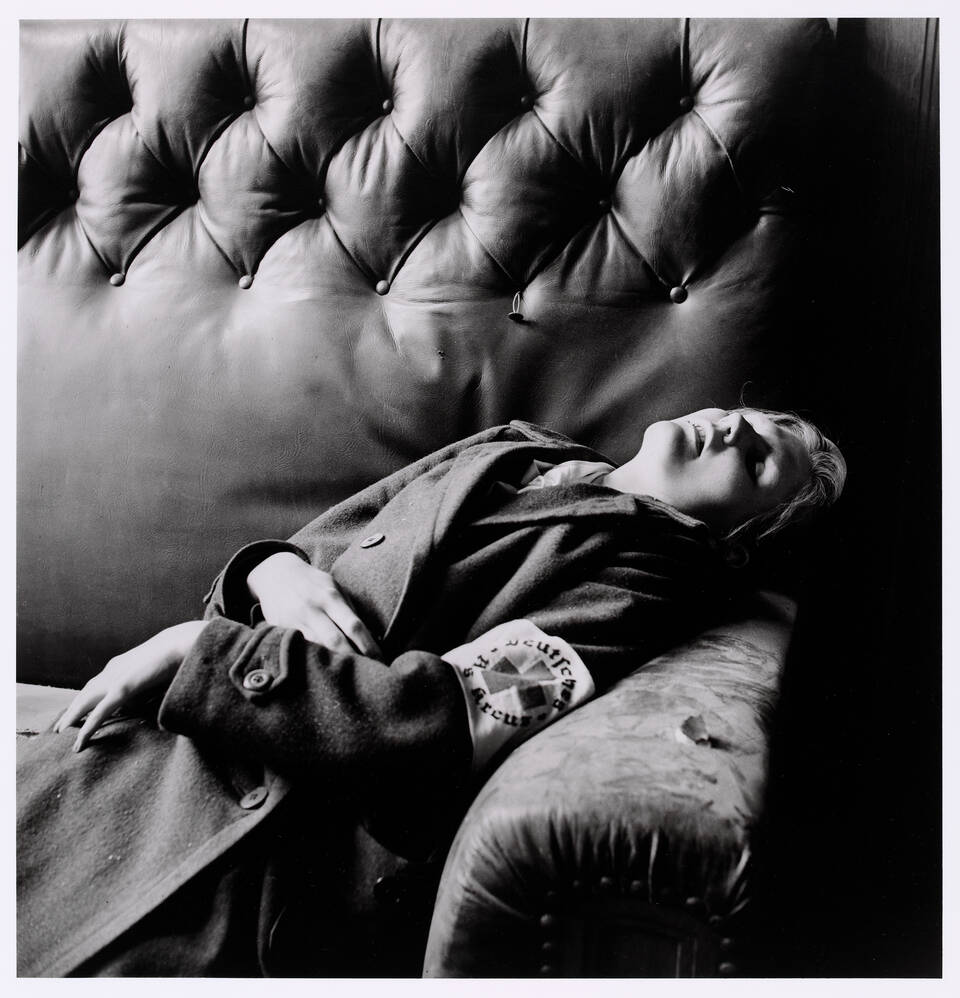

When Miller was accredited as a war correspondent in 1942, she became one of the few women to document the front lines of the conflict. Her work during this time was groundbreaking. Unlike many of her male peers, Miller’s photos often focused on the human cost of war. She captured the faces of soldiers, refugees, and survivors with a sensitivity that reflected her deep empathy for her subjects. Her images from the liberation of concentration camps, including Dachau and Buchenwald, are among the most harrowing ever taken. They bear witness to the horrors of the Holocaust in a way that words cannot fully convey. You can see this in her approach to composition, with her close ups of scenes usually taken form afar to provide context. take these two, the one of a dead soldier sunk in a river, and of a Nazi wife, who had committed suicide after hearing of The Nazi collapse, both images peaceful, despite the horror they depict.

It was against this backdrop of devastation and moral reckoning that the Hitler bathtub photograph was taken. The image’s power lies in its contradictions. Her presence in the frame transforms the act of bathing—a mundane, intimate ritual—into a statement of defiance. On another level, the photograph is profoundly political. By placing herself in Hitler’s private space, Miller subverts the power dynamics that defined the Nazi regime. Her muddy boots on the pristine bathmat symbolize the intrusion of reality into the carefully curated facade of Nazi propaganda.

But the photograph is not without its critics. Some have questioned the ethics of using Hitler’s private apartment as a backdrop for what could be seen as a performative act. Others argue that the image risks trivializing the atrocities committed under his regime. These critiques, however, fail to account for the context in which the photograph was taken. Miller and Scherman had just come from Dachau, where they had witnessed scenes of unimaginable suffering. The photograph was not a celebration but more of a coping mechanism, a way for them to process the horrors she had seen and reclaim a sense of agency in a world that often felt beyond her control.

In the years following the war, Miller struggled to reconcile her experiences with civilian life. She suffered from depression and PTSD, conditions that were very poorly understood at the time. Her marriage to Roland Penrose, a British surrealist painter, provided some stability, but it was also marked by periods of turmoil. Miller’s photography career waned, and she turned her attention to other pursuits, including cooking and hosting lavish parties at their home in Sussex. It was only after her death in 1977 that her work began to receive the recognition it deserved. Her son, Antony Penrose, played a crucial role in preserving her legacy, curating exhibitions and publishing books about her life and career.

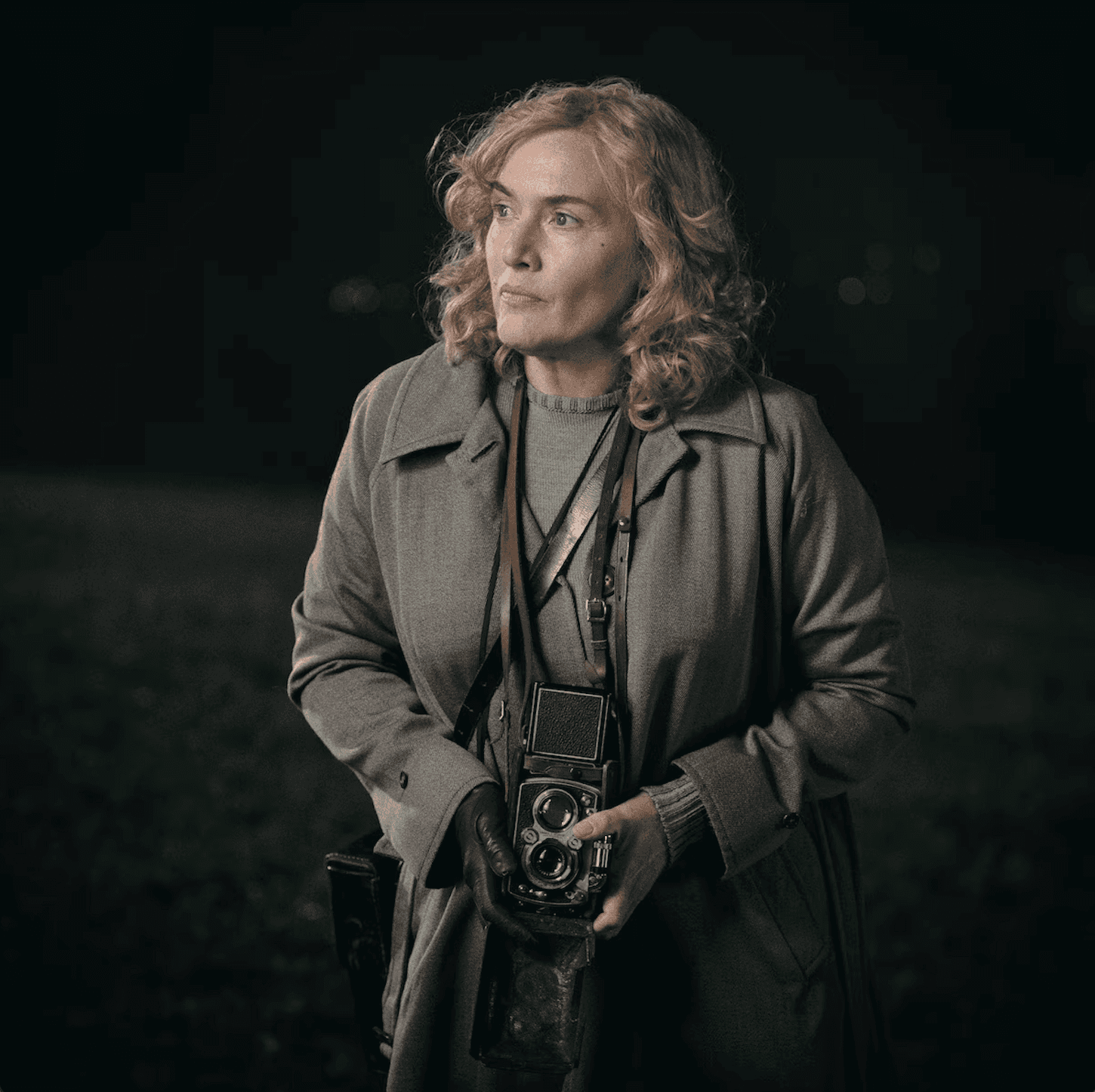

The upcoming biographical film starring Kate Winslet promises to bring Miller’s story to a wider audience. Directed by Ellen Kuras, the film seeks to capture the complexity of Miller’s character and the breadth of her achievements. The film will focus not just on Miller’s career but also on her personal struggles, providing a nuanced portrait of a woman who refused to be defined by any one aspect of her life.

The photograph of Miller in Hitler’s bathtub is still today one of the most amazing images of the 20th century. As the forthcoming film brings her story to a new generation, it is worth revisiting not just this iconic image but the remarkable life that led up to it. Lee Miller was close witness to history. Through her, we see the enduring power of art to challenge, provoke, and inspire.