Exploring the dark thrill of schadenfreude in the digital age, where public shaming and online mockery turn misfortune into spectacle.

By Rodrigo Garza

Oct 22, 2024

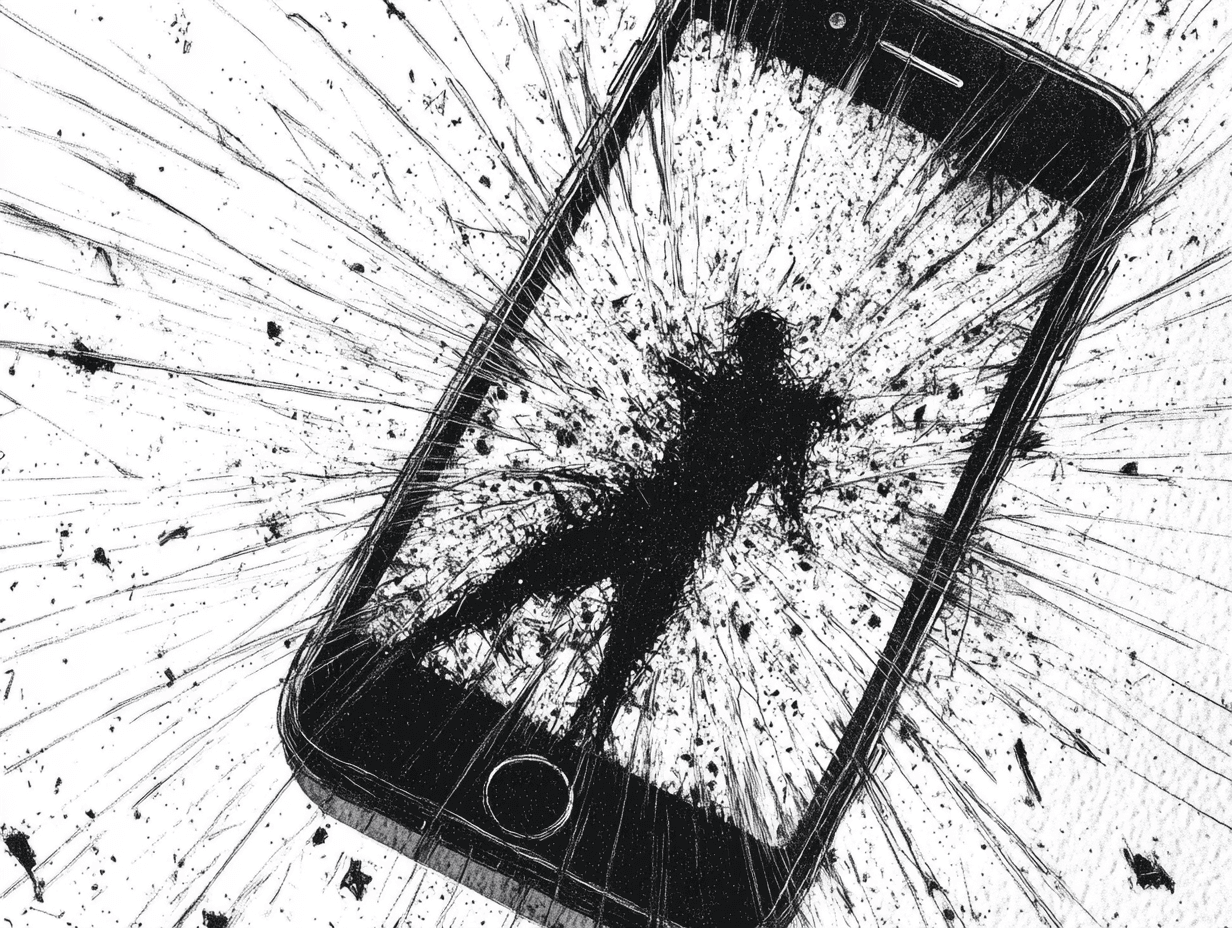

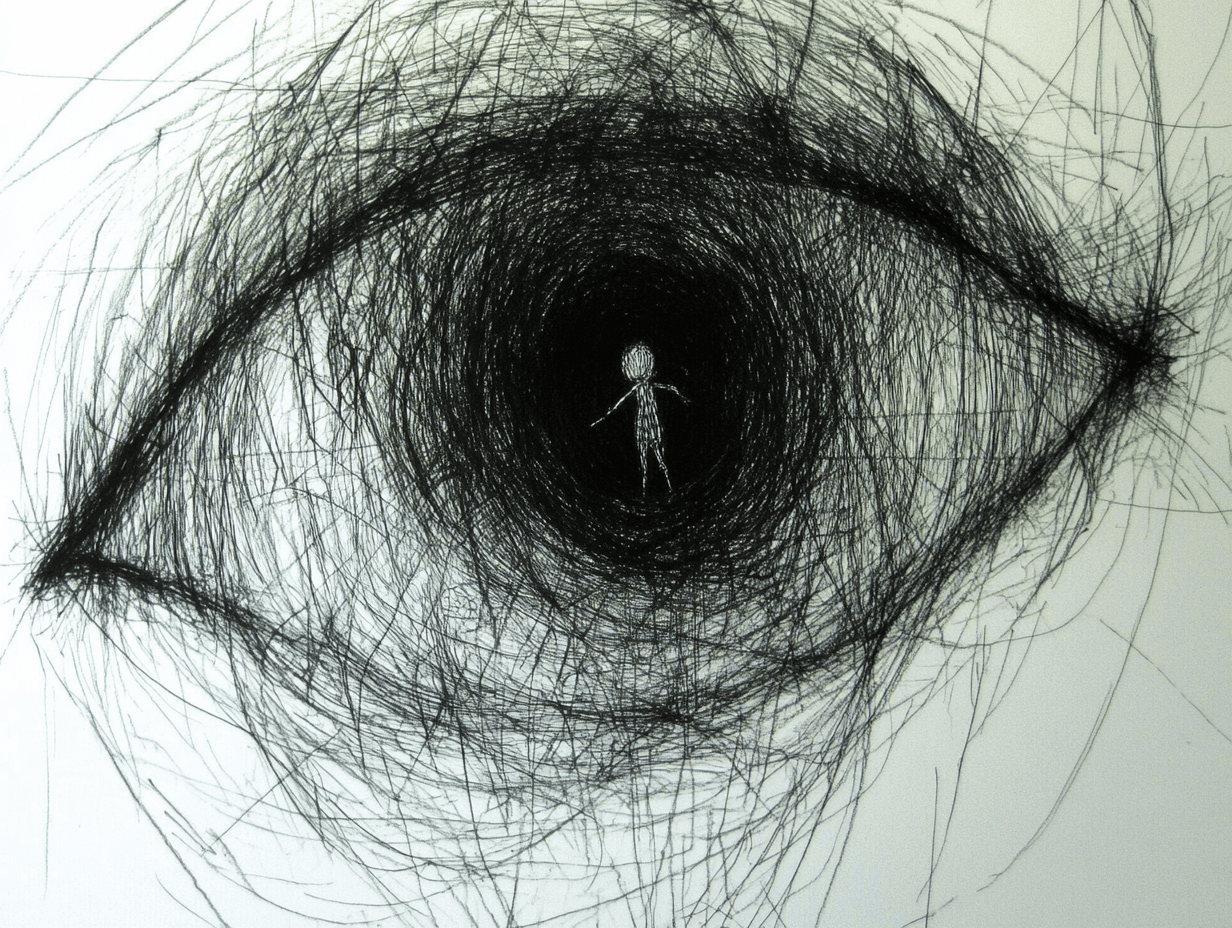

The Allure of Schadenfreude in the Age of Social Media

A mutilated body flashes across your screen—a grotesque snapshot of finality. Yehya Sinwar, leader of Hamas, reduced to flesh and blood, head blown out, lying in rubble, like a macabre trophy. Beneath the image, the comments section is throbbing with a dark energy . The joy is palpable—not the joy of peace restored or a world made safer, but something baser, something primal. This isn’t relief. It’s pleasure.

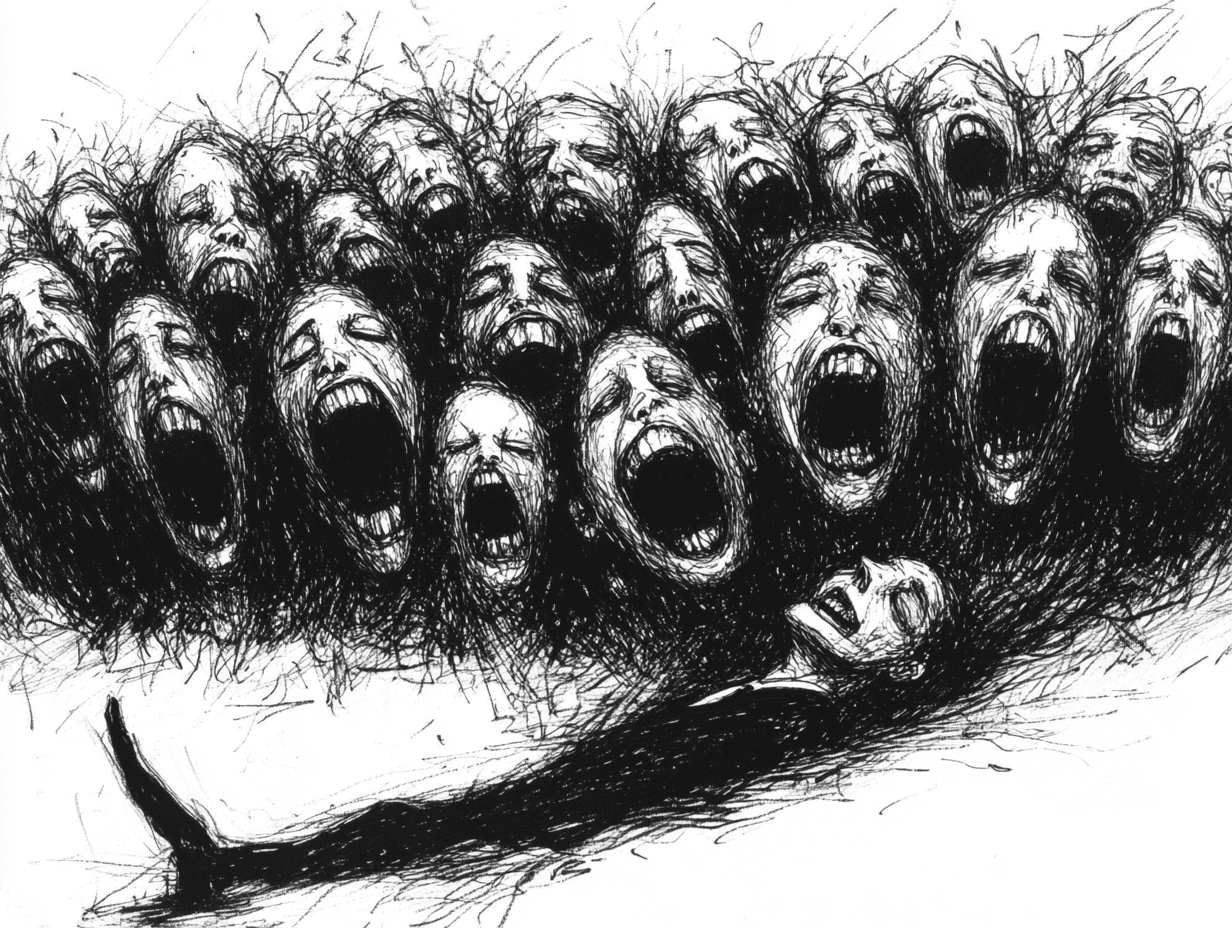

The image of Sinwar’s gored corpse, widely circulated on social media in October 2024, sparked a reaction that went beyond political discourse. Users didn’t just celebrate the end of a terrorist leader; they reveled in the violence inflicted on his body. It was a stark example of schadenfreude—a term borrowed from German, meaning “harm-joy,” or the pleasure we take in another’s suffering. On social media, schadenfreude isn’t a fleeting emotion; it’s a spectacle, a rush that brings people together in a shared, if twisted, sense of euphoria.

In the digital age, schadenfreude has found fertile ground, and particularly on twitter (now X.com). The internet allows us to witness misfortune in real-time, spread it at lightning speed, and participate in a collective celebration or mockery of the fallen, all without a second to think before acting. It’s not new—humans have always been drawn to the suffering of others—but the amplification and normalization of schadenfreude in online spaces have opened up new ethical challenges. Why are we so captivated by others’ downfalls? And what does this obsession reveal about our own humanity?

Understanding Schadenfreude

Definition and Origins

Schadenfreude is nothing new. The term may be German, but the emotion is universal and ancient. Throughout history, we’ve seen humans derive pleasure from the misfortune of others, whether in Roman gladiator arenas, medieval public executions, or the fall of disgraced politicians. It’s not just a passive feeling; schadenfreude often emerges when someone perceived as deserving punishment—rightly or wrongly—meets their downfall.

Today’s hyper connected society has shifted this dynamic. While public humiliations once required physical attendance and an active effort to go out of your way, they now unfold online, where millions can spectate, comment, and contribute. Listen, I didn’t ask to see the inside of Sinwar’s skull, i didn’t visit rotten.com, i just unconsciously opened Twitter before bed, jeez. The viral spread of Sinwar’s death, just like countless political scandals and celebrity meltdowns before it, becomes part of an ever-churning feed where public failures are put on display, and schadenfreude is the main event.

Psychological Foundations

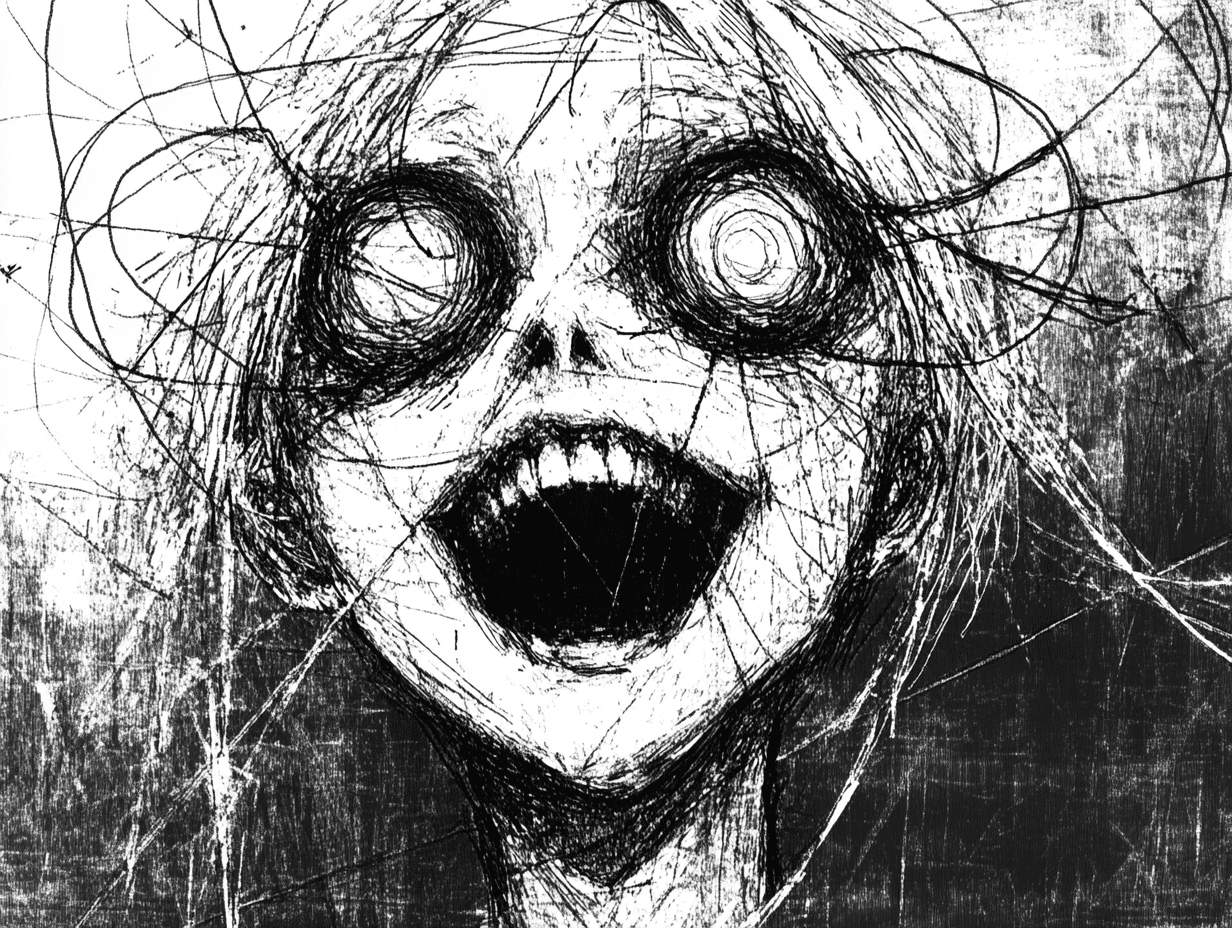

But why do we feel this way? Psychologically, schadenfreude has deep roots in human nature. It stems from the evolutionary need for social comparison, helping us navigate hierarchies and reinforce our own sense of superiority. Witnessing the downfall of a powerful or morally corrupt figure offers us relief—it reaffirms that justice, in some bizzarre sense, is served.

Social media has turned this into a dopamine-fueled cycle. Every like, retweet, and comment on a public humiliation is a hit, a validation that we are on the “right” side of the moral divide. But it’s not just about satisfaction or justice; it’s also about self-worth. Watching someone more powerful, more successful, or more notorious fall from grace boosts our own self-esteem. We feel more secure, more important. In an online world that constantly makes us feel inadequate, schadenfreude is an easy fix, but sure, keep telling yourself how you would have done things better.

Factors Contributing to Schadenfreude Online

Feelings of Justice and Moral Superiority

The most obvious driver of schadenfreude online is the perception of justice. When someone seen as immoral or corrupt faces a downfall—whether it’s a politician, a celebrity, or a corporate tycoon—the sense of moral retribution kicks in. In the case of Sinwar, many justified their glee with the belief that he deserved his fate for leading Hamas into the October 7 terror attacks. For these users, the visceral pleasure in seeing his mutilated body was not just accepted; it was righteous.

It taps into a broader trend in online spaces: virtue signaling. By openly celebrating the downfall of controversial figures, users align themselves with a sense of moral superiority. Social media has turned this into a performance, where broadcasting outrage becomes a way of establishing group identity and sense of belonging. In this context, schadenfreude is not only an emotional response but a tool for reinforcing group dynamics—particularly in the age of “wokeism,” where moral stances are performative and subject to public approval.

This has led to the creation of a digital feedback loop: the more public and vocal the schadenfreude, the more validation one receives from their peers. It’s not just about punishing the “enemy”—it’s about showing the world that you’re on the right side of history, that you belong to the morally superior in-group, pissing on the enemy’s grave if it will put you up top.

Envy and Resentment

Not all schadenfreude comes from feelings of moral superiority, though. Much of it is rooted in envy and resentment. Social media constantly bombards us with images of success, wealth, and power. We see the lives of the rich and famous and can’t help but feel small in comparison. So when these larger-than-life figures fall, it’s cathartic. The taller the poppy, the more satisfying it is to see it cut down.

In Sinwar’s case, while few in the West would have envied his political life, his power as a militant leader certainly made him a figure to be toppled. And for those who see themselves as victims of injustice, as oppressed by corrupt powers, the fall of someone like Sinwar feels like a personal victory, even if it’s distant and removed from their own lives. And it happens regardless of political stances, there were people celebrating the October 7 massacre because Gaza was breaking free of oppression.

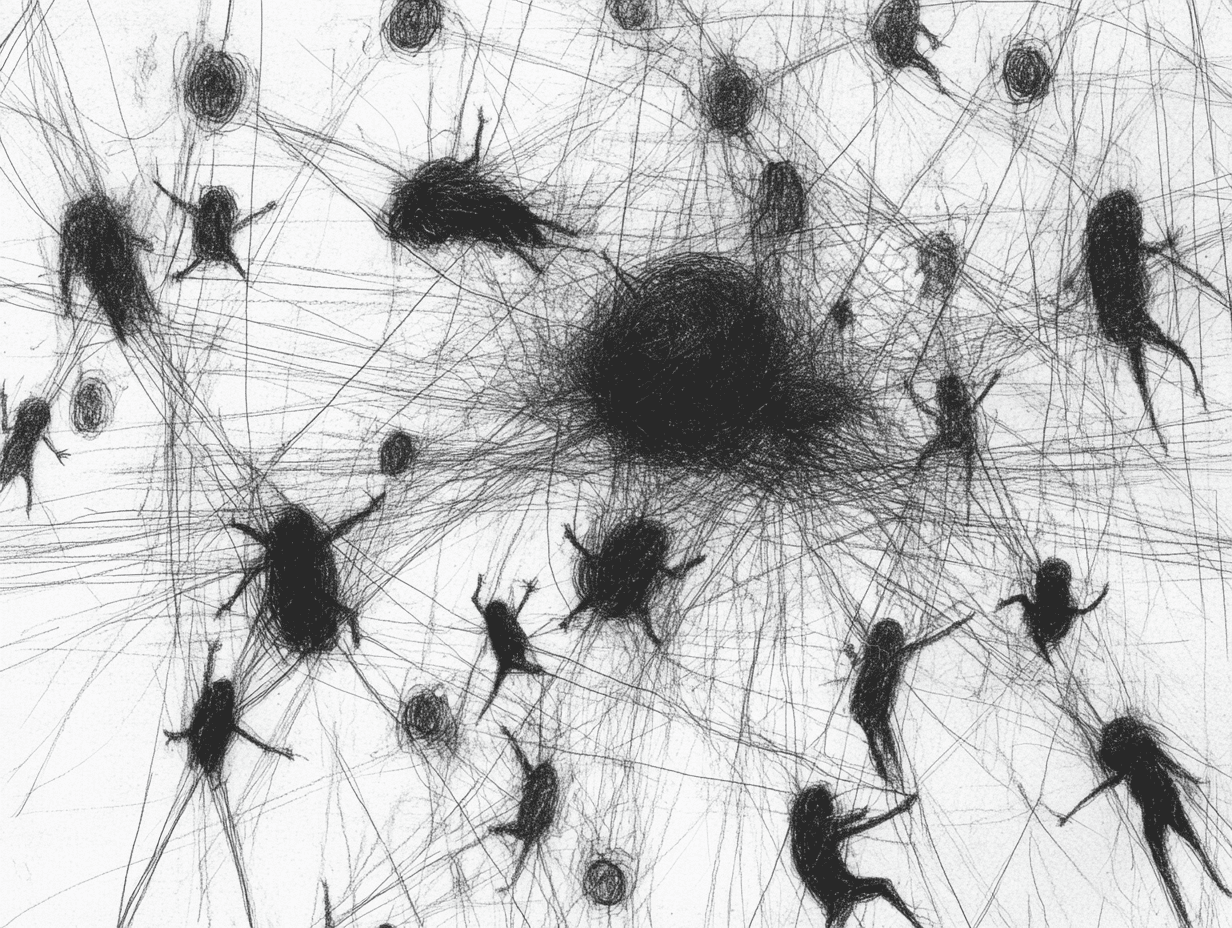

Amplification by Social Media Dynamics

What makes schadenfreude so potent in the digital age is its amplification by social media dynamics. Platforms like X are designed for rapid, viral sharing. When Sinwar’s death photo circulated, it didn’t just spread quickly; it spread with emotion. Anger, joy, and shock collided in the same space, fueling engagement and boosting visibility.

Add anonymity to the mix, and the ethical barriers that normally govern human interactions begin to crumble. Behind the veil of a username, users feel free to express extreme emotions that they might otherwise suppress in face-to-face settings. The anonymity of the internet strips away the empathy cues we’d naturally pick up in real life, allowing schadenfreude to flourish unchecked.

The Role of Desensitization

Overexposure to Misfortune

We’ve become desensitized to misfortune. Social media, with its endless streams of bad news, has numbed us to suffering. When images of war, tragedy, and scandal hit our feeds every second, it’s easy to become emotionally detached. The shock value wears off. Misfortune becomes entertainment. And in a place where everything is content, everything—including suffering—is consumable.

The photo of Sinwar wasn’t just another news story; it became part of the endless scroll. A gruesome image, sure, but surrounded by memes, celebrity gossip, and sports highlights, its impact diluted by its context. This constant overexposure to misfortune erodes empathy. When everything is a spectacle, nothing feels real.

Impact on Empathy

As a result, we’re witnessing a cultural shift: the slow erosion of empathy. Schadenfreude thrives when empathy wanes. The more we engage in collective mockery, the harder it becomes to relate to the suffering of others. Compassion fatigue sets in, leaving us numb to the human cost behind the images and stories that flood our screens. This desensitization has profound implications for how we connect—not just online, but in real life. The more we revel in others’ pain, the further we stray from our own humanity.

Cultural and Ethical Implications

Global Reactions and the Politics of Public Misfortune

Schadenfreude is not just a Western phenomenon. Public reactions to the fall of controversial figures vary across the globe, shaped by cultural, political, and social contexts. The viral spread of Sinwar’s death, while celebrated in certain Western circles, elicited a different reaction in parts of the Middle East. For some, it represented the ongoing cycle of violence and political oppression that has defined the region for decades. Here, schadenfreude doesn’t simply play out on Twitter—it’s tied to the lived experience of conflict, occupation, and survival.

In authoritarian regimes, schadenfreude can also become a tool of power. Public executions or humiliations are designed to provoke fear, but they often trigger collective glee. The downfall of political dissidents or enemies of the state isn’t just state-sanctioned punishment; it becomes a public spectacle that reinforces the regime’s control. Here, schadenfreude isn’t just an emotion—it’s a form of complicity.

Ethical Considerations

This brings us to the heart of the ethical dilemma. When is it acceptable to celebrate another person’s death? Does the perceived justice of the situation—like the fall of a terrorist leader—justify the cruelty of our reactions? And more importantly, what happens to us, as individuals and as a society, when schadenfreude becomes the default mode of response to public failures?

Online, it’s easy to feel distant from the consequences of our actions. But each time we revel in someone else’s suffering, we contribute to a broader culture of mockery and dehumanization. At what point does this culture erode our collective empathy beyond repair? The normalization of schadenfreude is a slippery slope—one that leads to a society where cruelty is not only accepted but expected.

Addressing Schadenfreude in the Digital Age

Personal Reflection and Growth

The first step in addressing schadenfreude is introspection. We need to ask ourselves: *What am I contributing to when I share, like, or retweet a post that mocks someone’s misfortune?* The ease with which we can engage in schadenfreude online often obscures the larger ethical implications of our actions. Personal reflection means acknowledging the small ways we participate in a culture of public shaming, whether by laughing at a cruel meme or reveling in the downfall of a public figure. To combat this, we need to cultivate empathy deliberately, training ourselves to respond to misfortune with understanding rather than mockery.

One way to foster this shift is through mindfulness. Before engaging in online discussions, we can pause to consider: Am I adding value, or am I contributing to a cycle of cruelty? Mindfulness encourages us to break the automatic response of sharing or amplifying negativity and instead encourages thoughtful, compassionate engagement.

Another practice is perspective-taking—actively trying to understand the emotions and experiences of those who find themselves in the spotlight. In the case of Sinwar’s death, perspective-taking might mean considering the broader context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or the devastating loss of life on both sides, rather than zeroing in on a single moment of violent retribution.

Role of Social Media Platforms

Social media platforms also bear responsibility for curbing the spread of schadenfreude. Their algorithms are designed to prioritize engagement, which often means that the most emotionally charged—and often negative—content is what surfaces. If platforms took steps to promote positive, constructive interactions, they could help shift the culture toward one that values empathy over mockery.

This could take the form of algorithmic adjustments that deprioritize posts celebrating violence, humiliation, or suffering, instead elevating content that fosters understanding and dialogue. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram already employ community guidelines to curb harassment and hate speech, but these guidelines should be expanded to address the subtler forms of cruelty that schadenfreude represents.

These initiatives could promote digital literacy and encourage users to reflect on their behavior online, challenging them to engage with empathy and critical thinking. Platforms can also design campaigns that emphasize compassion and responsible engagement, setting a new standard for online behavior. Sure, I know these initiatives sometimes might seem useless and probably won’t move the needle in any significant way, but they’re worth exploring.

Cultural and Ethical Implications

Global Reactions and the Politics of Public Misfortune

The ethical questions surrounding schadenfreude are complicated by global perspectives. In the West, where individualism and the notion of personal accountability dominate public discourse, there’s often a simplistic, black-and-white view of justice: people get what they deserve. But in other parts of the world, reactions to public downfalls are shaped by different cultural narratives and historical experiences.

In societies that have experienced long-term conflict or oppression, public schadenfreude can carry a different weight. The death of a political leader or a figure like Sinwar may trigger emotions tied to cycles of violence and loss, emotions that are far more complicated than simple glee. For many in the Middle East, Sinwar’s death is not just the end of a terrorist—it’s another moment in a seemingly endless conflict where loss and suffering are constant companions. In these contexts, schadenfreude becomes entangled with grief, anger, and trauma.

We must also consider how authoritarian regimes use schadenfreude as a tool of control. Public executions, shaming rituals, or the downfall of political dissidents are carefully choreographed spectacles designed to evoke both fear and satisfaction. The collective celebration of a dissident’s downfall becomes a way for the regime to reinforce loyalty, turning schadenfreude into a political weapon.

In all these cases, schadenfreude is not just a psychological phenomenon—it’s deeply political. It reflects the power dynamics of the world we live in and serves as a reminder that the emotions we feel online are often manipulated by larger forces.

Ethical Considerations

Ultimately, schadenfreude raises difficult ethical questions about our capacity for empathy in a world where public humiliation is increasingly treated as entertainment. Can we, as a society, claim to value human dignity when we so readily engage in public shaming? And more pressingly, what kind of world are we building if our first instinct in the face of someone else’s downfall is to laugh rather than to understand?

We must reckon with the long-term consequences of indulging in schadenfreude. When we engage in these cycles of public humiliation, we risk normalizing cruelty and dehumanization. Every time we share a mocking meme or pile onto a trending takedown, we are contributing to a cultural shift that prioritizes spectacle over substance, division over empathy.

The ethical challenge before us is to resist this impulse. It’s easy to dehumanize others, especially in the faceless, fast-paced world of social media. But what we need now, more than ever, is to pause, reflect, and ask ourselves: What does it mean to be human in the digital age?

Confronting Our Role in the Culture of Schadenfreude

It’s easy to scroll past a viral meme mocking a fallen public figure, to chuckle at the latest scandal, to engage in the collective catharsis of watching someone else fail. But have you ever paused to ask yourself why? Why does someone’s misfortune bring you pleasure? How many times have you hit “like” or “share” without thinking about the consequences—not for the person being mocked, but for what it says about you? The uncomfortable truth is that schadenfreude isn’t just an online spectacle—it’s a reflection of who we are, of what we allow ourselves to become in the digital space.

It’s tempting to distance ourselves from the more extreme examples—the public celebrations of a terrorist’s death, the vicious takedowns of controversial figures. But schadenfreude doesn’t start with these grand moments; it starts with the small, everyday decisions we make online. It’s the retweet of a snide comment, the laughing emoji on a teardown post, the casual remark that dismisses another’s pain as deserved.

The next time you see a moment of public humiliation—whether it’s Amanda Bynes, President Biden or Sinwar losing their heads—ask yourself: *What am I really celebrating?* Is it justice? Or is it something darker, something that reflects more about your own insecurities and need for validation than any larger moral victory?

Would you say this out in public to a person’s face?

Here’s a thought: choose not to participate. Don’t share the meme. Don’t add to the chorus of shit talk. In fact, take a step further—challenge the culture itself. When you see others basking in someone’s misfortune, call them out, although without shaming. Ask the uncomfortable questions: Why are we celebrating this? What does this say about us?

This is not just a call for empathy and humanity—it’s a call for accountability, it’s what liberalism stood for back in the day. In the end, schadenfreude might feel good in the moment, but it leaves behind a cultural residue that erodes our collective humanity. If we want to create a better digital space—one where we lift each other up rather than tear each other down—it starts with the small, quiet decision to resist the pull of cruelty. In the end, the people we mock aren’t even reading your nasty incel comment. But you are typing it out and sharing it, and doesn’t matter who receives it.

The choice is yours: continue scrolling, laughing, and sharing without a second thought, or pause—reflect—and just think for a bit before shitposting. Please.