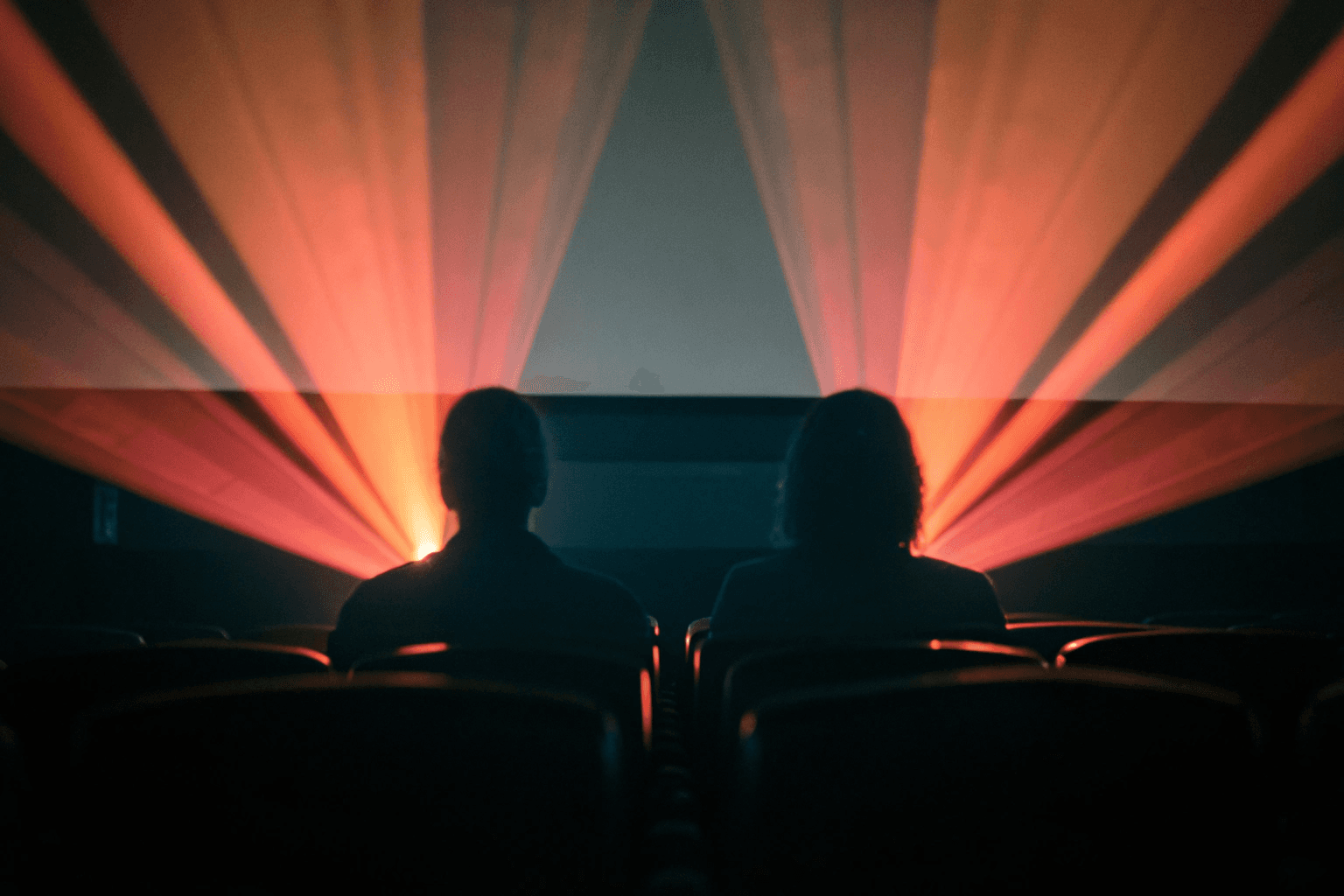

Want to sharpen your taste in life? Movies can teach you more than you think—design, storytelling, and style start here. 🎥✨

By Rowan March

Nov 18, 2024

Developing a unique taste through film isn’t about memorizing random bits from Reservoir Dogs or striking a Wes Anderson pose against the nearest pastel wall in your sight for your IG. It’s about watching movies, I mean really watching them. With an analytical eye, a film stops being just entertainment. It becomes a blueprint, and a chance to refine your taste and reimagine how you see this chaotic world—much like a great painting does. This is about cultivating an appreciation for aesthetics, embracing what inspires and provokes you, and finding beauty even in what unsettles you, and not less important, being able to have an original thought.

Defining Your Own Sense of Beauty

Aesthetic isn’t just for film students, critics, or snobs. Everyone has taste, to some extent, even if you don’t know it yet. But it’s buried, covered up by algorithms and mindless doom-scrolling while binge-watching. Watching films with a critical eye can help unearth and nurture your taste, showing you what you’re drawn to and, more importantly, why you’re drawn to it. Think of it this way: every close-up, color palette, awkward cut, or line of dialogue speaks to something in your subconscious—even if you’re not listening. And hey, we don’t want to judge, bit If you’re watching “It Ends With Us”, and Marvel movies, as your main diet, your taste will develop, but it will develop to be just like everyone else’s, (tinfoil hat alert) driven by capitalism and corporate agendas.

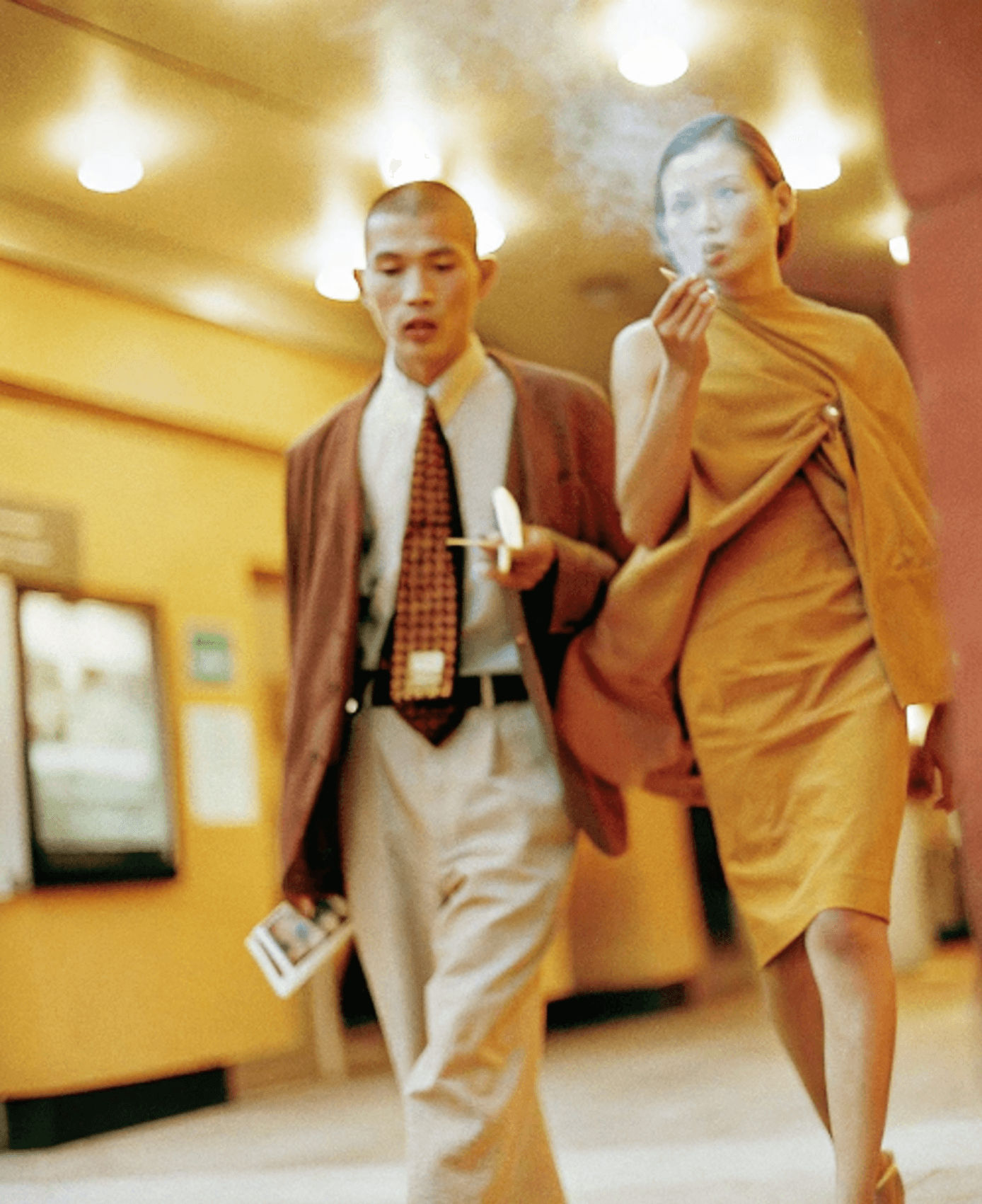

Here’s a tip, take Mark Cousins’ approach to film studies. He suggests that developing an eye for aesthetic starts with color. Spend a week studying the use of color in different films: from , yes, the surreal pastels of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, but also the high-contrast blues and reds of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love. You’ll notice how each director uses color to create mood and tell a story visually, teaching you to recognize the power of color in all forms of art.

Start by picking a theme—like color or sound. Watch two or three movies with this focus in mind. Why does the stark black-and-white of Schindler’s List create such an emotional impact? What do Tarantino’s high-saturation palettes do to the feeling of violence in Kill Bill? Write down your impressions, even if they’re not fully formed. You’ll start seeing how certain aesthetics resonate with you more than others, be aware of them.

Expanding Your View of the World

Every film is a portal into a different life, culture, or philosophy. And in a world that’s increasingly polarized, the ability to step outside your comfort zone and empathize with others is important. Watching films from different countries and eras can be a way of pushing your boundaries and challenging assumptions.

Look at the films of Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami. His work, like Taste of Cherry and Close-Up, plays with moral ambiguity, creating space for viewers to question their own beliefs and preconceptions. Kiarostami’s characters often face moral dilemmas that leave you wrestling with your own. Or take Tokyo Story by Yasujirō Ozu, a deeply minimalist yet universal story about family and aging. The film’s slow pacing forces viewers to really sink into each scene and confront universal themes of distance and disconnection within family ties.

Pick three films from countries you know little about. Watch them back-to-back, focusing on the characters’ lives and values. Ask yourself, how are their perspectives different from yours? Do you sympathize with them? Why or why not? This can be as simple as trying Bollywood’s Dangal to see family and pride in a new way, or Korean classics like Oldboy to experience unfamiliar emotions and narrative arcs, or Mustang, another great option.

Watch Like a Critic

Watching movies critically doesn’t mean you’re becoming a pretentious asshole. Watching critically means engaging with a movie on a deeper level, allowing yourself to really feel and reflect, just like being mindful in real life, be mindful during viewing. Ask questions, why did that scene resonate? Why did it fall flat? It’s not about memorizing technical jargon; it’s about listening to your own reactions and figuring out what they mean.

Tarantino’s style has been dissected a million times, but it’s still worth mentioning because it shows how aesthetic and taste are deeply intertwined. Tarantino loves to play with violence—not just in terms of bloodshed, but in how he makes it look. In Pulp Fiction and Inglourious Basterds, violence becomes beautiful, seductive, and often darkly funny. You can love or hate it, but it’s undeniably distinct. When a scene repels you or draws you in, that’s worth analyzing.

After watching a movie, jot down the moments that struck you, and go into why. Was it the way the shot was framed, the music that played, or the actor’s delivery? Compare it with another film. Soon, you’ll notice patterns and start to understand your unique aesthetic preferences.

The “Taste Muscle”

Think of taste like a muscle—it needs workouts to grow. Watching movies critically and repeatedly helps you sharpen these aesthetic instincts. Absorbing elements of style, noticing patterns, and developing an instinct for what appeals to you.

Hitchcock’s obsession with suspense is legendary. Movies like Vertigo, Psycho, and Rear Window play with pacing, subtle visual clues, and offbeat characters to build tension. Watching several Hitchcock films back-to-back reveals the recurring techniques and tricks he uses to keep audiences hooked. Once you see it, you start noticing similar suspense techniques in newer movies, developing an instinct for effective pacing.

Try a director deep-dive. Spend a week or two watching only one director’s films. Write down stylistic themes or elements they revisit—Scorsese’s New York, Kubrick’s meticulous framing, Lynch’s dreamlike surrealism, Ari Aster’s ability to unsettle, Panos Cosmatos’s metal neo noir, Terrence Malick’s american ethereal This immersion is an intense exercise for your “taste muscle” and will give you a distinct sense of each director’s style.

Go Beyond the Algorithm

Streaming algorithms are designed to keep you hooked, not to develop your taste. But taste isn’t built on familiarity. It’s built by going beyond the mainstream and seeking out films that push you out of your comfort zone.

Here’s Cousins’ suggestion of a “50 weeks to learn film” structure. You don’t need an intensive course; you just need a few categories to guide your viewing. Pick movies that go deep into these themes and focus on analyzing how they handle each one.

A few tips before jumping in, open your mind to watching movies that are in black and white, or impossibly slow, or in another language, or silent, or unstructured, or too melodramatic, or musicals, or Dogma 95, or too religious and too satanic.

Mark Cousins “50 weeks to learn film”

(originally published on bfi.com)

1. A week on colour: Goethe’s ideas about contrasting hues, and the colours in shadows; colour in nature, in the beaches of Harris and Lewis in Scotland; costume and design in the movies of Jacques Demy.

2. Eyeline: Oliver Hardy looking at the camera, the eyelines of the Madonna in Russian icon painting (they look almost at the viewer but not quite), eyelines in the films of George Cukor and Ozu Yasujiro.

3. Wedding films: many of the most profitable films ever made (judged by percentage return on investment) are about weddings – The Wedding Banquet, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Monsoon Wedding, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Muriel’s Wedding, Bridesmaids, Mamma Mia!. What can we learn from why they work?

4. Nude figure drawing.

5. Focus: in Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Hitchcock, Kira Muratova, Leonardo da Vinci and Mantegna.

6. Obsessive motifs: Scorsese on Lower Manhattan, Picasso on the face of Dora Maar, Lyonel Feininger on the church at Gelmeroda. The students choose a motif and make a different film about it every day.

7. Nature studies: Scandinavian films of the 1910s, the work of Albrecht Dürer, the writing of Rousseau.

8. Thought: in Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Federico Fellini, Scorsese and Forough Farrokhzad.

9. Storytelling, blocking and emotion in 13th- and 14th-century Italian painting: Duccio, Cimabue, Giotto (including a trip to the Scrovegni chapel).

10. Walkabout: each student disappears, goes off grid, for a week, with no means of communication.

11. Other: each student lives a life or has an experience that is totally foreign to them.

12. Kick the truth out: The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, and how to show what you aren’t allowed to show.

13. The sublime: in Werner Herzog, Caspar David Friedrich and Burke.

14. Storytelling in three-minute pop songs: The Kinks, Squeeze, PJ Harvey.

15. The art of persuasion: how to charm officials to let you in to places (includes Herzog’s advice that you should always “carry bolt cutters everywhere”).

16. Tension in storytelling: Hitchcock, Stephen King, Patricia Highsmith, Mohammad-Ali Talebi.

17. Poetics: in Aristotle, David Lynch, Le Corbusier and Pier Paolo Pasolini.

18. The mirth of nations: comedy cinema around the world.

19. Vengeance and violence: in Djibril Diop Mambéty, Quentin Tarantino and John Woo.

20. Movement and blocking: in the films of Tsui Hark, King Hu and Orson Welles, and the paintings of Tintoretto.

21. Sound poetics: in the movies of Kira Muratova, Paul Thomas Anderson and Hitchcock, and the work of Walter Murch.

22. Music week: taught entirely in the dark.

23. “What might never have been seen”: Films that showed lives that had never before been on screen – the work of Kim Longinotto, John Sayles, Anand Patwardhan and Kenneth Anger.

24. Voice, and how to find it: the distinctive look and feel of the movies of John Ford, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Michael Mann, and the paintings of Francis Bacon.

25. Performance: A whole week on the film by Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammell, which will include the students undergoing changes.

26. How to end a film: 2001, the endings in Ozu films, Claire Denis’s Beau travail, Imamura’s Tales from the Southern Islands, Antonioni’s L’eclisse, Billy Wilder’s The Apartment.

27. The psychology of crying: crying and pathetic fallacy, Douglas Sirk, trying not to cry, and the ending of It’s a Wonderful Life.

28. LSD: those students who want to, take acid and allow themselves, if they want, to be filmed. The experience then leads to studies of Kandinsky, musique concrète, surrealism, David Lynch, Maya Deren and Jonathan Glazer films.

29. Iconoclasm and media portrayals: a visit to Esfahan in Iran.

30. Interview: filmmakers conduct interviews and are, regularly, interviewed themselves. So this week is a study of the best interviews ever done, in film, TV, radio and print. The Paris Review, Paul Morley, Face to Face, etc.

31. Secret: a study of films with secrets, such as The Crying Game, Vertigo, The Usual Suspects, Kiarostami’s ‘Koker’ trilogy. How do plot twists, or style twists, work, and what are the best ways to do them? This week should, itself, contain an unexpected twist for its students.

32. The frontier: students go and live for a week on the island of Lampedusa, or another place of migratory movement where human rights are being abused.

33. Sex: how to do sex in cinema, looking at Courbet’s L’Origine du monde, the sex scenes in Jean-Luc Godard, Catherine Breillat and Souleymane Cissé.

34. Lubitsch: five of his silent masterpieces, and why they work.

35. Panic and calm: the psychology of fight or flight, and its opposite, and its depiction in story and cinema – Tsui Hark, Apichatpong, and the performances of Jack Lemmon.

36. The human face: how to look at it, film it, hide it, in the paintings of Rembrandt, the films of Rohmer, and the performances of Gong Li, Ruan Lingyu and Hideko Takamine.

37. Memory: in Shakespeare, Sergio Leone, the masterpieces of Guru Dutt, Moufida Tlatli and Alain Resnais.

38. Self: should I put myself into my film? The movies of Agnès Varda, François Truffaut and John Ford, and the writing of Virginia Woolf.

39. Literal: how to avoid on-the-nose dialogue, story signposting and gong metaphors.

40. Silent: a week not speaking at all. “I tell stories not to speak, but to listen” – Rudiger Vogler in Alice in the Cities.

41. Beginnings: the great openings in cinema, and why they work – Blue Velvet, Kaagaz Ke Phool, Psycho, etc.

42. Costume and story: In the Mood for Love, The Conformist, Jezebel, The Red Desert, Throne of Blood.

43. Recut: re-editing great films that are flawed because of bad pacing or endings, or too many endings, or extraneous scenes – Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds, Kwaidan, the Brazilian film Limite, etc.

44. Rescore: great movie scenes given new sound and music tracks – the shower scene in Psycho, the ending of Tarkovsky’s Mirror, the opening of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, the whole of The Jungle Book.

45. Life: Kierkegaard, De Beauvoir, Lao Tzu, Montaigne, George Eliot, Bentham, Clarice Lispector, Amartya Sen, Jesus Christ, Jung, Walter Benjamin, Joseph Brodsky, Merleau-Ponty.

46. Love: in the work of Samira Makhmalbaf, Joan Didion, Frank Borzage and Howard Hawks.

47. Death and grief: in The Ballad of Narayama, J-horror, Amour, Three Colours Blue, The Babadook, Gravity.

48. Watch Kieslowski’s Dekalog and ten films directed by Stanley Donen, alternating one of each.

49. The turning of the Earth: the magic moments of the year. A recap of what we have learnt.

50. Destroy: the students burn their notes from the 50-week course, and write the themes and outline for next year’s 50 weeks.

Listen, we get it, it’s a long fucking list, but if your attention span can’t handle it, get back to TikTok, and who knows, maybe your algorithm on there is amazing, kudos to you. Otherwise, how about choose one theme a week and find two or three films that fit that theme. As you watch, focus on how the theme is presented. By curating a “syllabus,” you give yourself a taste workout without needing to enroll in a formal course. These are only suggestions, hopefully by the time you get half way through this list, you’ll know to add some of your own choices to the list.

Why Cultivating Taste Through Film Is About More Than Movies

Developing taste is about using movies as a gateway to building your own aesthetic POV for everything you encounter in life. Taste in film will translate to taste in music, art, books, interior design, even fashion. Once you start thinking critically about one medium, you’ll naturally apply that level of awareness to everything else.

Directors like Kubrick and Lynch have aesthetics so distinct they bleed into other realms. People who love Kubrick’s symmetrical, masterfully crafted visual style often appreciate and start noticing balance an lighting’s role in everyday situations, like taking a random photo on the subway, you’re getting that vanishing point just right, or bringing out the candelabra for a nice dinner. Viewers of Lynch’s eerie, surreal worlds are often drawn to music, literature, and art that feels equally unsettling. Your taste in film can set the tone for how you curate your entire life, or in today’s terms, build your real-life algorithm.

Building Taste as a Lifelong Practice

Developing taste is about learning how to engage critically and emotionally with everything you see and do. It’s about finding what resonates with your sense of beauty, storytelling, and emotion (what are we without emotion?)—and using that to shape how you interact with the world. Whether you start by diving into Cousins’ guide, exploring niche global cinema, or just paying closer attention to the details in your next Netflix binge, the point is to keep digging, keep watching observing, and keep challenging yourself. Taste is a muscle. Start working it out. And for the love of all that is good, watch something other than than Selling Sunset every now and then.