La Rosa de Guadalupe contrasts divine intervention with the bleak, tech-driven worlds of Black Mirror and The Twilight Zone—faith vs. fear?

By Rodrigo Garza

Oct 15, 2024

Unless you’re Latino, chances are you’ve never had the fortune to come across La Rosa de Guadalupe, if you have, you’ve probably found yourself dumbfounded, for the rest of you, buckle up. For context, in La Rosa de Guadalupe (The rose of the Virgin of Guadalupe) Every episode follows the same formula: a problem—usually one that involves modern vices like addiction, bullying, unholy teenage lust, or, yes, having a black child—emerges.

There’s melodramatic suffering, a whole lot of bad acting, and then, right when things get dire, a miracle: a white rose appears, the Virgin Mary’s presence manifests in a heavenly gust of wind, and everything’s fine again, Deus Ex Machina at its very finest, Hallelujah.

This wildly popular Mexican anthology series has been running since 2008, with over 1,500 episodes under its belt. It’s like if you mixed soap operas, Catholicism, and after-school specials, then sprinkled on a heavy dose of “Fuck rationality.” It’s preachy, melodramatic, and—honestly?—addictively weird.

But what’s even more fascinating to me is how La Rosa de Guadalupe sits in stark contrast to similar anthology shows around the world. Let’s get one thing straight: La Rosa is nothing like Black Mirror, The Twilight Zone, or even Amazing Stories. Those shows are about reflecting back society’s darkness, giving you a taste of modern fears, from tech dystopias to existential crises, cool, but a bit cliché. Want something truly original? La Rosa de Guadalupe. This would be exactly what your grandmother’s TikTok Algo would look like.

The Story Behind La Rosa de Guadalupe’s Heaven-Sent Success

For the creator (of the show) Carlos Mercado, La Rosa de Guadalupe wasn’t meant to be the fever dream of religiousness it’s become. It started off as an ode to the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s patron saint and an embodiment of Mexican Catholicism. Her image is a source of comfort and protection, so naturally, Mercado thought, why not build an entire TV show around people in shitty situations praying to the Virgin and having their problems magically solved?

The show’s religious overtones are a reflection of Mexico’s deeply entrenched Catholic roots though. In a country where faith often intertwines with daily life, La Rosa de Guadalupe gives viewers what they crave: divine intervention. The show hits its audience right in their religious G spot, offering comfort that when the world goes to hell (literally or figuratively), the Virgin Mary will be there to sort it all out.

And for over a decade, people have kept tuning in. Why? Because no matter how absurd the show gets, it delivers on what it promises: hope, faith, and a resolution. Sure, it’s corny, but who the hell cares, in the world of La Rosa, everything works out if you just believe. I like to think of it as an antidote to the ridiculously unhealthy social media feeds showing us a different global cataclysm every day. It a balance, if you will.

The Twilight Zone (and Its Unholy Offspring)

Now, let’s talk about the other side of anthology Television. Back in 1959, The Twilight Zone hit American screens, bringing with it a blend of psychological horror, sci-fi, and moral lessons wrapped in eerie, thought-provoking narratives. Created by Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone wasn’t interested in miracles—unless you count the miracle of human stupidity. Serling used the show as a way to reflect the anxieties of mid-century America: fear of nuclear war, suspicion of technological advancement, and a general distrust in humanity.

Each episode of The Twilight Zone followed a standalone story, often ending with a dark twist or ironic moral. If someone was arrogant, they’d get their comeuppance. If they tinkered too much with fate, they’d be punished. It wasn’t a hopeful universe. And, unlike La Rosa de Guadalupe, where everything gets tied up with a neat little miracle bow, The Twilight Zone often left viewers feeling uneasy—like there was no higher power to save us from ourselves. Sound familiar? It should, because Black Mirror is its modern-day, nihilistic heir.

San Junipero vs. La Rosa de Guadalupe’s Happily Ever After

To really understand how La Rosa de Guadalupe differs from global anthology shows, let’s compare two episodes: San Junipero from Black Mirror and any given episode of La Rosa (but let’s take the classic episode titled “La Bendición de Dios” for good measure).

San Junipero is one of the rare episodes of Black Mirror that doesn’t leave you feeling like you need a stiff drink and a therapy session afterward, its the center of a ven diagram between these two shows.

It’s a love story set in a virtual afterlife where people can live forever in a version of reality that they choose. In this world, queer love finds its place, and two women, Yorkie and Kelly, manage to escape death by transferring their consciousnesses into this digital paradise. There’s no God here, but there’s still a kind of transcendence—albeit one delivered by tech instead of divine intervention.

But San Junipero is no fairy tale. The episode leaves viewers grappling with questions about mortality, identity, and whether eternal life is worth it if it’s only a facsimile of reality. Sure, Yorkie and Kelly get their happy ending, but it’s a bittersweet one wrapped in existential dread. There’s no miraculous gust of wind signaling that the Virgin Mary is cool with your decision to upload your consciousness to the cloud.

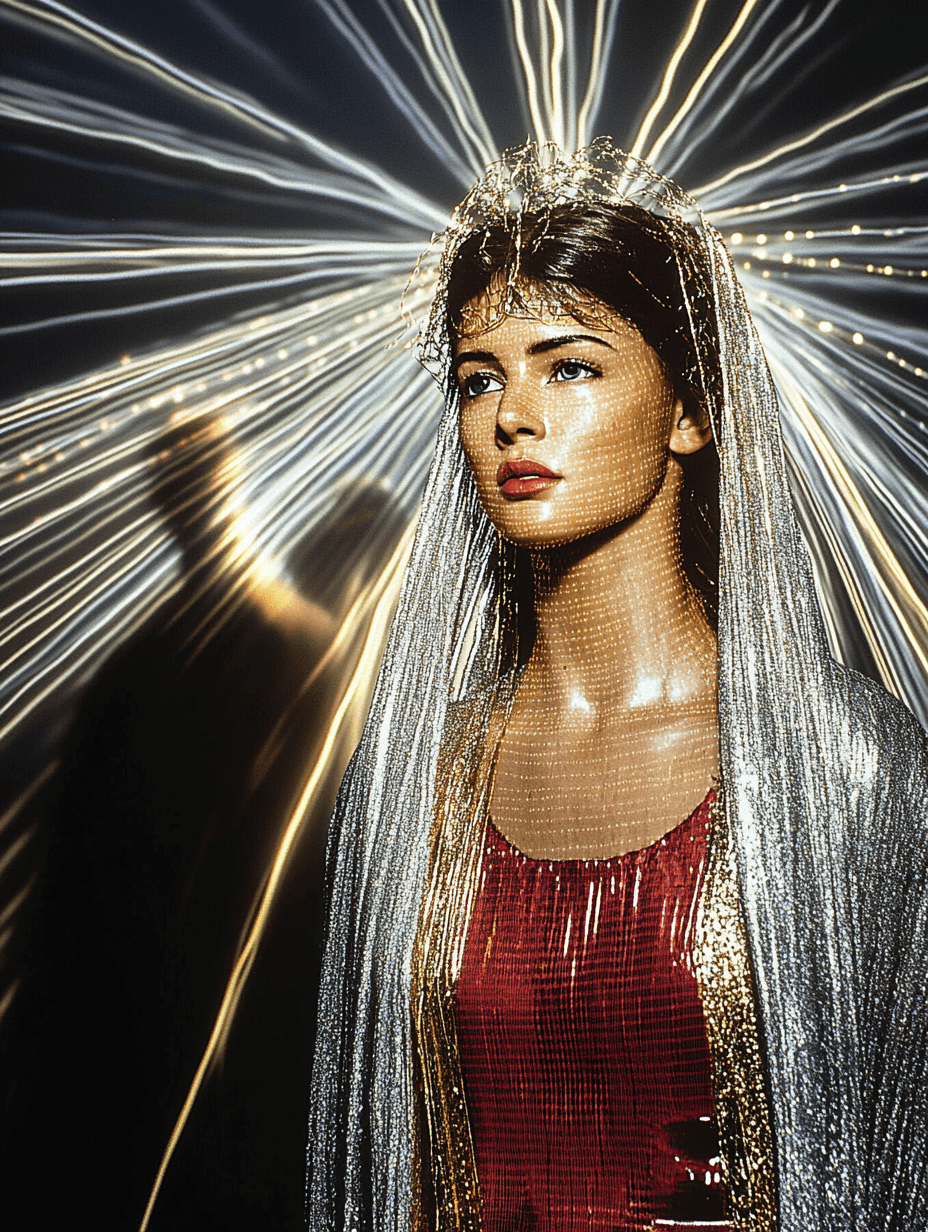

Now, in “La Bendición de Dios,” we see a family facing severe hardship. There’s abuse, financial instability, and a whole lot of crying. After a series of grim events, one of the characters prays to the Virgin Mary, and lo and behold, she answers with a gust of wind, the appearance of a white rose (just like the cover of this article) , and suddenly all their problems disappear. The abusive husband is transformed into a loving partner, the financial problems are solved, and the family lives happily ever after. No deep questions asked—just pure, uncut, Catholic-approved faith.

This is where the difference lies: in Black Mirror and The Twilight Zone, you get questions, doubts, and moral ambiguity. In La Rosa de Guadalupe, you get answers, and those answers are simple: pray, believe, and your life will get better. It’s not subtle, but it’s effective for the show’s target audience. Also, as far as actionable takeaways, you can pray al you want, but you cant upload your consciousness anywhere yet, or get a talking sex doll of your dead spouse yet, but we’ll get there, i’m sure. “Hey Siri, spread those cheeks”.

The Holy vs. The Hellish

The real difference between La Rosa de Guadalupe and shows like Black Mirror isn’t just in the storytelling—it’s in the worldview. La Rosa presents a world where divine forces are constantly at play. If you’re a good person, if you suffer enough, God will come through. You can almost hear the Catholic guilt whispering, “If things aren’t getting better, maybe you aren’t praying hard enough.” religious escapism at its finest.

Meanwhile, in Black Mirror and The Twilight Zone, there’s no such divine intervention. The only “miracles” that happen are the result of human ingenuity or, more often than not, hubris. In these worlds, the gods have long since abandoned us—or maybe they never existed in the first place. We’re left to fend for ourselves, and that usually means screwing things up in spectacular fashion. Black Mirror makes it clear that our problems aren’t going away with a quick prayer. If anything, they’re about to get worse, it’s basically Bill Maher vs. Jordan Peterson, but without incels.

The Showrunners: A Battle of Worldviews

The creator of La Rosa de Guadalupe, is very much a product of his cultural environment. Born and raised in Mexico, he’s steeped in the country’s Catholic traditions. He believes in the power of faith, and his show reflects that belief. Orduña created the show as a response to the moral and social issues facing Mexico, offering divine solutions to problems that plague modern society. His goal isn’t to scare viewers or challenge their faith—it’s to reinforce it.

On the other side of the spectrum, you’ve got Charlie Brooker’s worldview, decidedly more cynical, with his show often serving as a dystopian warning against the dangers of technology and humanity’s darker instincts. For Brooker, the idea of divine intervention is laughable. In his world, there’s no higher power coming to save us from the mess we’ve created. We’re on our own, and it’s not looking good.

Rod Serling, the creator of The Twilight Zone, falls somewhere in between. While his show is often bleak, it’s also deeply moralistic. Serling was concerned with the human condition, but he never suggested that faith alone could save us. Instead, his stories often focused on the consequences of our actions—whether it was our own hubris, greed, or fear that did us in.

Our Top LRDG most outlandish stereotypes brought to the big screen:

The Emos

The Otakus (Anime Kids)

The Stoners

The Gays

And the best… Racist parents

La Rosa De Guadalupe Is a very Cristian show, of the catholic strain, and some episodes can be ridiculous, like when the Virgyn Mary decided to help not on ly in spirit, but to manifest in body for that extra help, or like “El Ritmo Del Pecado” (the rhythm of sin), which is about the vulgarity of Reggaeton culture among teenagers, and even borderline racist on occasion, like on the episode “Un corazón no tiene color” (A heart knows no color), about a teenage pregnancy with more plot twists than an early M. Night Shayamalan movie, where it turns out, the baby is born Black, to two hispanic teens, and then, the teenage father goes on a rant because his son is black, shouting, “¿Que? ¿Es negro?, ¿mi hijo es negro?” (What?, he’s black?, my son is black?). This scene became a very popular meme, and upon conducting research for this piece, I discovered that this anthology storyline is revisited on 3 occasions, and I’m not one to leave you hanging, they keep the child, drama ensues first with the Father coping with having a black child when the grown child inquires about his skin color, putting the young couple through the wringer a few more times, always assisted by the Virgin Mary.

The World Needs La Rosa de Guadalupe… and Black Mirror

Ultimately, La Rosa de Guadalupe and shows like Black Mirror exist on opposite ends of the storytelling spectrum, but both serve a purpose.

La Rosa de Guadalupe gives its audience the comfort of knowing that even when things get tough, divine intervention is just a prayer away. It reinforces the idea that there’s a higher power looking out for us, ready to step in and fix things when they go off the rails. It’s pure escapism, and sometimes escapism is exactly what we need.

Black Mirror, on the other hand, forces us to confront the darker side of our nature and the dangers of the modern world. It’s not trying to offer solutions—it’s trying to make us think about the consequences of our actions. Where LRDG wraps things up with a miracle and a happy ending, Black Mirror leaves you questioning everything you thought you knew about society, technology, and the future.

And maybe that’s the point. For every audience that finds solace in La Rosa de Guadalupe’s divine solutions, there’s another that thrives on Black Mirror’s dystopian warnings. One show offers a vision of the world where everything can be fixed with faith; the other reminds us that we’ve got no one to rely on but ourselves. Either way, they both speak to the deepest fears and desires of their audiences—and isn’t that what TV is all about?