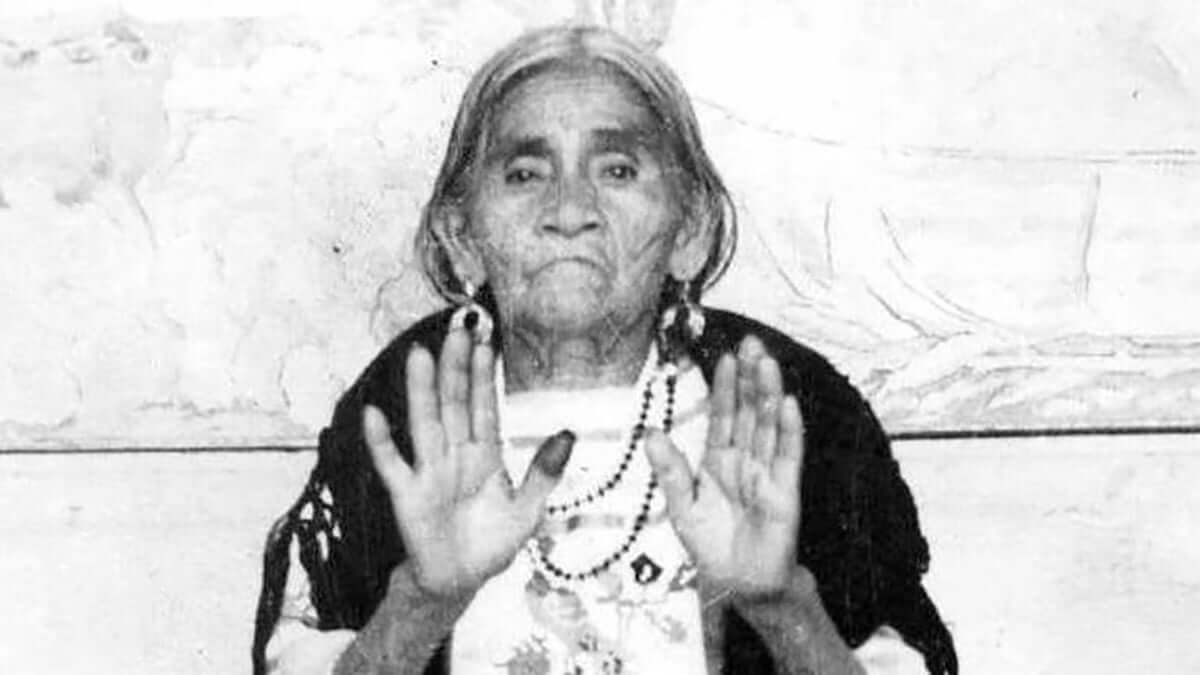

María Sabina, The Mexican healer, who unintentionally sparked a global psychedelic movement. Her sacred mushroom ceremonies—and life—paid the price.

By Rodrigo Garza

Oct 25, 2024

It’s a familiar story by now—Western white dude stumbles into an ancient indigenous culture, co-opts their traditions, and brings them back to his world where he becomes famous and wealthy, back in the day, maybe a Tim Leary type, these days, a white guy with dreadlocks. Meanwhile, the indigenous people get to keep their anonymity, get ostracized, or at best, turned into myth once they’re dead.

María Sabina's story is that exactly. She was the Mazatec curandera or Chamana, a healer from a tiny village in Oaxaca, Mexico, who unwittingly became the catalyst for the global psychedelic movement that flooded the 1960s. But the price of fame was far more bitter than sweet for her. For Sabina, the ritual of mushroom consumption was part of a larger, more intricate web of spiritual practice that had been passed down for generations. This was not a recreational or experimental “trip”; it was a tradition rooted in the very identity of the Mazatec people. The “veladas”, or mushroom ceremonies, which Sabina led, were meant to heal the sick, bring clarity in times of crisis, and connect with the divine—whether that meant the spirits of ancestors or otherworldly entities. The shrooms themselves, known as niños santos ("holy children"), were not simply substances to be ingested, but they were seen as sacred guides that facilitate access to other realms.

The veladas were also performed in a specific manner. Under the cover of darkness, the sacred space was prepared, often accompanied by candles and chants in the Mazatec language. The experience was deeply spiritual, not hallucinatory in the way most Westerners might expect their “trip” to be. The mushrooms functioned as a conduit to the spiritual plane, but the focus was on healing the mind, body, and spirit, rather than pursuing a detached or euphoric high. For the Mazatec people, there was an inherent respect and even fear associated with these ceremonies. They were not entered into lightly.

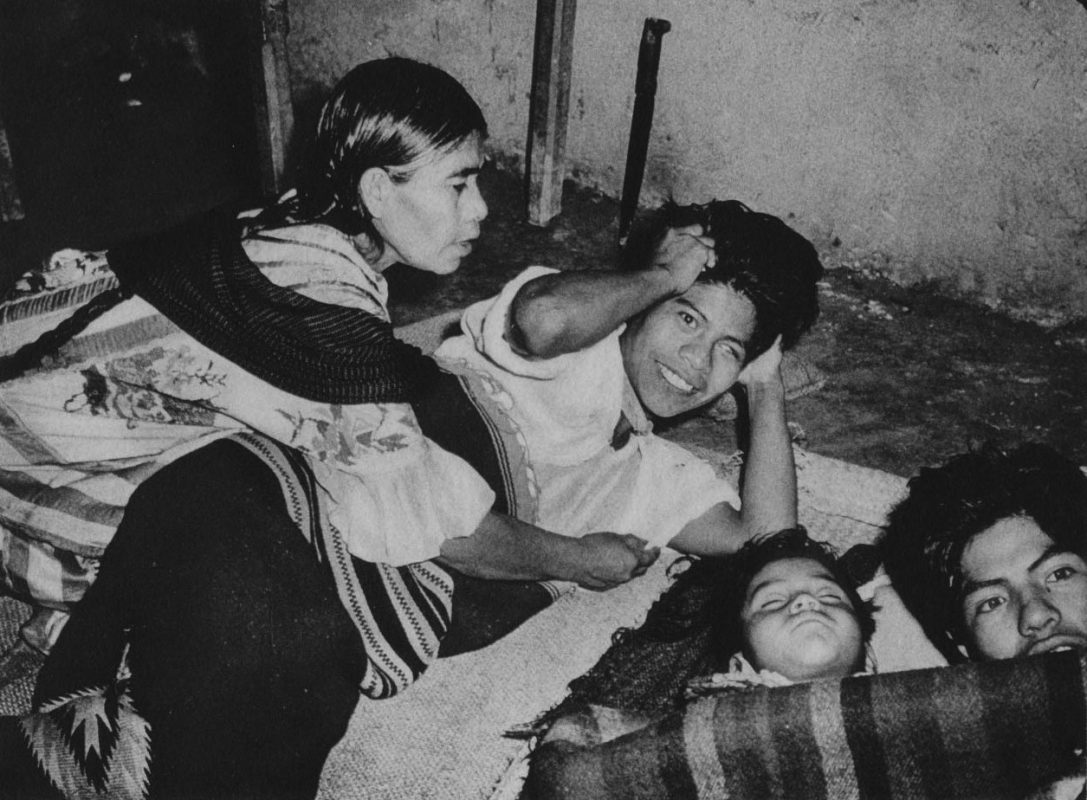

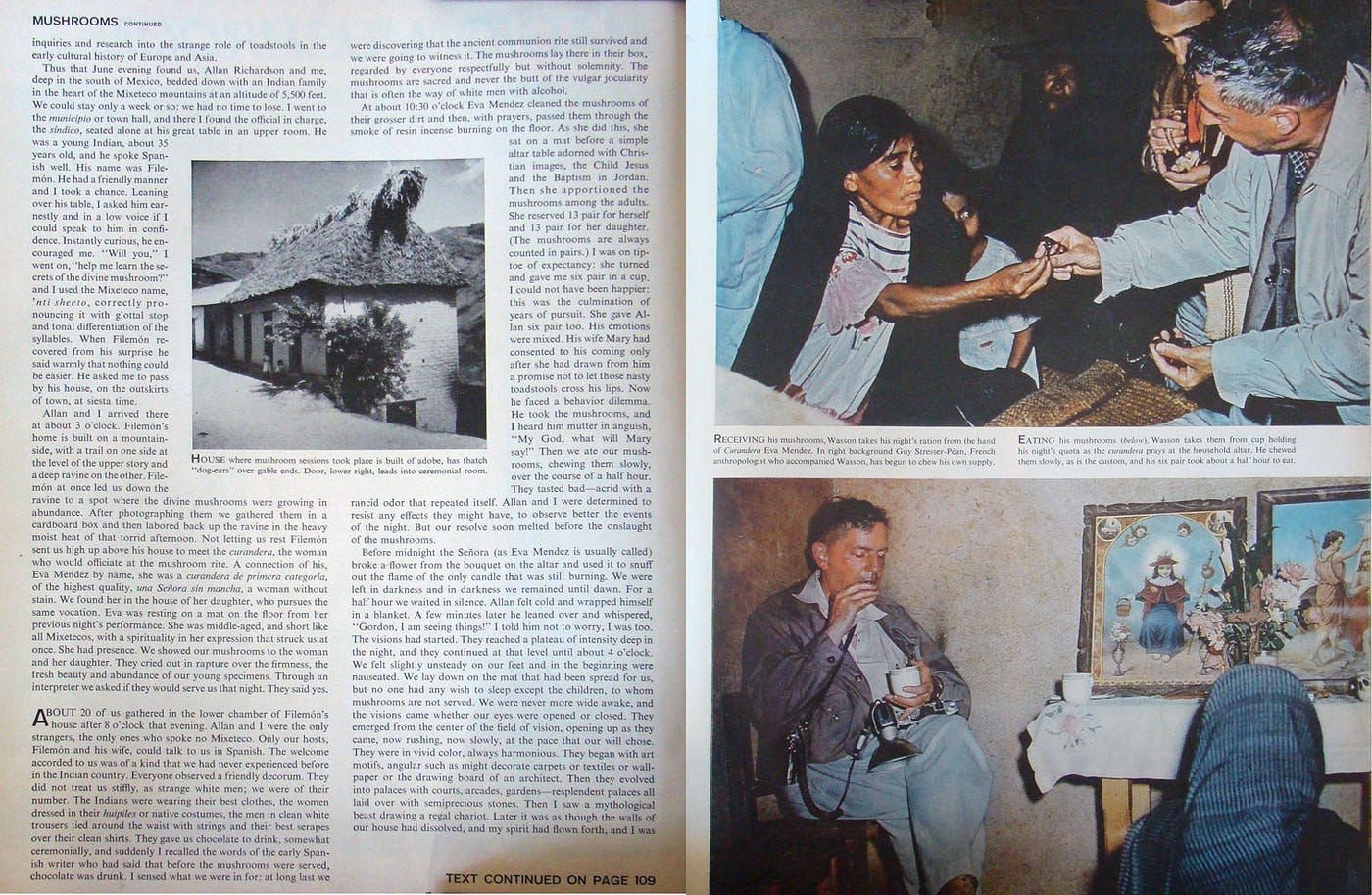

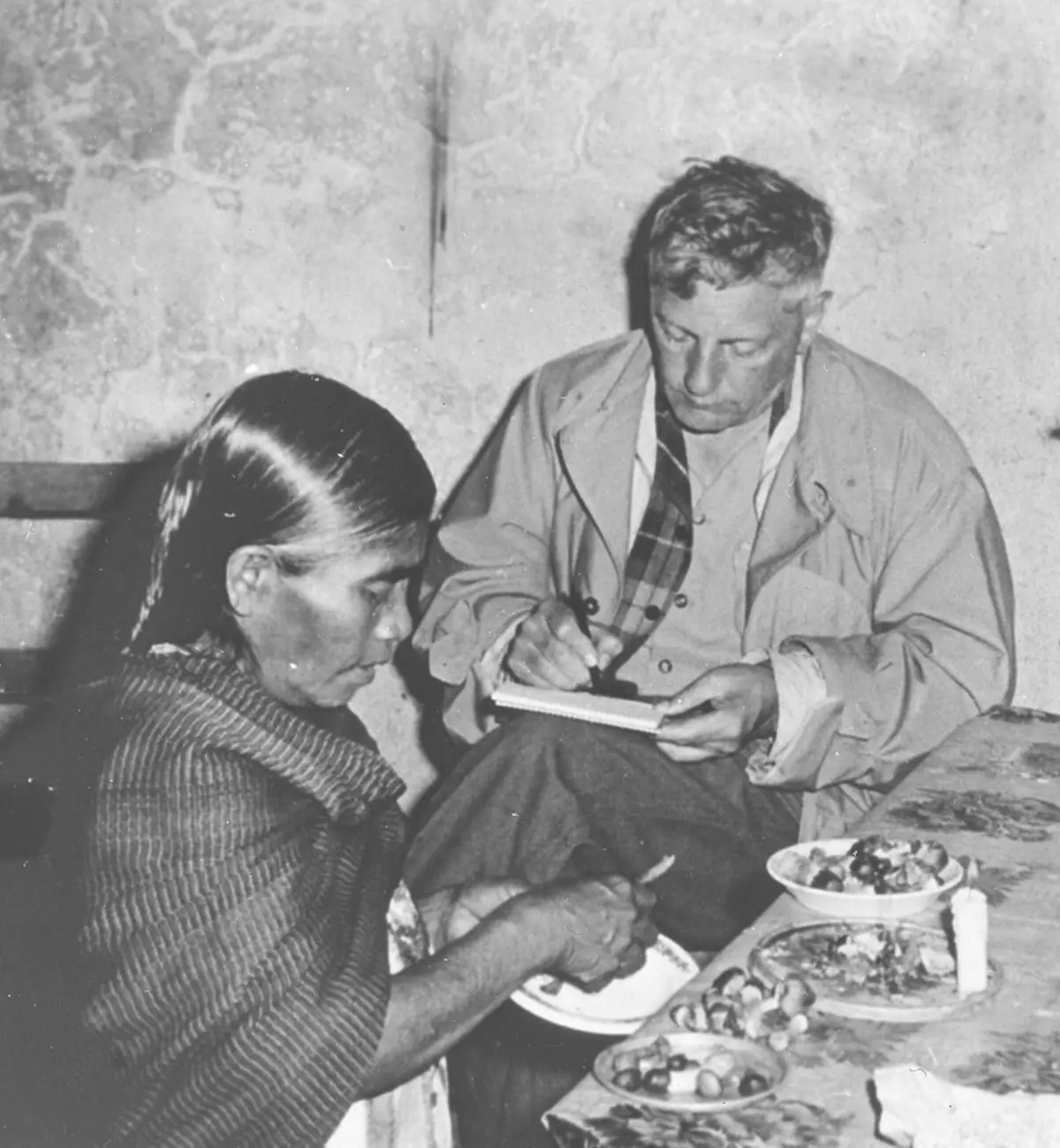

This context is crucial because it frames Sabina's subsequent experiences with outsiders, starting with R. Gordon Wasson in 1957. Wasson was not the first outsider to seek out Sabina’s help, but he was one of the most consequential. The rituals of the Mazatec people had, for the most part, remained hidden from the modern world—a deliberate choice given the long history of colonial oppression and cultural exploitation that indigenous communities had faced for centuries. Wasson’s fascination with mushrooms, through his wife, however, led him on an exploratory mission. He came to Mexico with a mixture of curiosity, reverence, and, let’s be honest, a desire to uncover something ‘exotic’ for the Western world. What began as a personal quest quickly spiraled into something much larger.

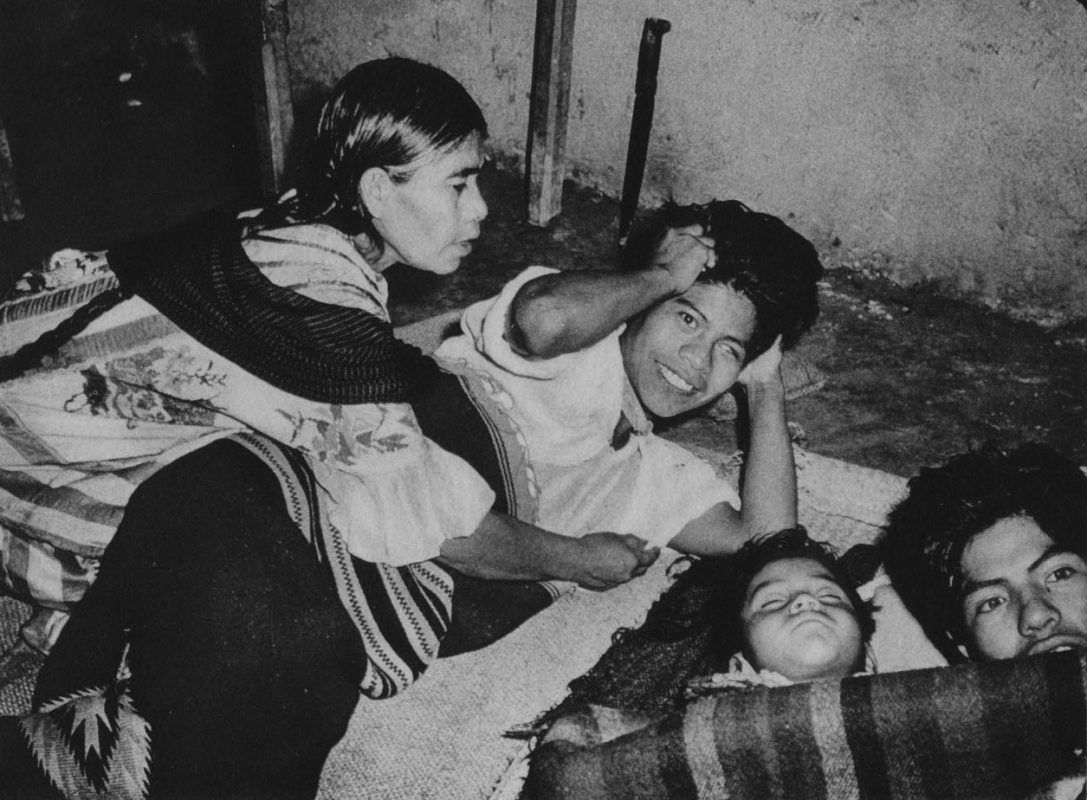

Wasson, along with his photographer Allan Richardson, participated in one of Sabina's veladas. Wasson had been collecting data on the cultural significance and use of mushrooms in various societies, but his experience with Sabina went far beyond his academic interests. The ceremonial consumption of the psilocybin mushrooms opened a door into a dimension of consciousness he had not anticipated. Sabina’s chants, her invocations of spiritual forces, and the profound effects of the mushrooms themselves left a lasting impression on Wasson, and within two years, his article "Seeking the Magic Mushroom" was published in Life magazine.

The article, with its evocative descriptions and photographs of Sabina in her element, accompanying the participants, her young son among them, sent shockwaves through the Western world. For those already engaged in the burgeoning counterculture of the 1960s, the notion of a natural substance that could expand consciousness was irresistible. It was like gasoline thrown on a fire already crackling with discontent—discontent with societal norms, with the war machine, with the oppressive structures of Western capitalism. Psychedelics became a kind of shorthand for rebellion, for radical exploration of the self and the cosmos. Figures like Timothy Leary, Aldous Huxley, and eventually the entire hippie generation latched onto the idea that substances like psilocybin could unlock hidden dimensions of the human mind.

But while Wasson got credit for "discovering" the magic mushroom and countercultural icons used them to break down the barriers of the mind, María Sabina’s life went to hell. The spiritual sacredness of the veladas was lost on those who traveled in search of a mystical experience, leading to a barrage of psychedelic tourists arriving at her village in Huautla de Jiménez, rumored among them, Aldous Huxley, John Lennon, Jim Morrison, Walt Disney, Alejandro Jodorowski, Mick Jagger, among others. These outsiders were not just curious onlookers but people who believed that participating in Sabina’s ceremonies would grant them access to a state of enlightenment—a privilege that had previously been reserved for those within the Mazatec tradition or for those facing grave spiritual and physical ailments.

In Huautla, the sudden influx of outsiders—most of them white western men—upended the social fabric. The village, once remote and insulated, became the epicenter of a psychedelic pilgrimage. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the area was overrun by Hippies looking for the magic that María Sabina had facilitated.

This influx fundamentally changed the way the locals viewed Sabina. Her community, once supportive and reverent of her work as a healer, began to see her as a sell-out. The sacred mushroom, which had been central to their spiritual practices, had been turned into a commodity, a tool for outsiders to chase experiences rather than heal their souls.

Sabina was accused of betraying her people by opening their most sacred traditions to foreigners. Her home was even burned down in an act of retaliation, and she found herself ostracized by the very community she had dedicated her life to serving. The Western fixation on psychedelics transformed her from a respected healer into a scapegoat for her people’s woes. This was no longer about spiritual healing; it was about the clash of cultures, exploitation, and the devastating consequences of commodification.

I’m also guilty of this in a way, although I didn’t have the chance to have a velada with Sabina, I have partaken in the mushroom rituals in the Oaxacan Sierra, with Lupita & Manuel, my guides in the velada. And even though the experience was life altering I am just another tourist among the bunch, and no matter how much thought and depth I put into it, I’m no Mazatec, I’m a hispanic white man. But that’s a story I’ll tell on another time.

In interviews later in life, Sabina expressed her profound sadness over the changes that had swept through her village. She claimed that the mushrooms had lost their power—that their purity had been sullied by the greed and disrespect of outsiders. The deep reverence for the niños santos that once marked her ceremonies was replaced by a kind of psychedelic tourism that had little regard for the spiritual significance of the rituals. María Sabina, who had once been a gatekeeper to the divine, became a tragic figure—a woman whose gifts were co-opted by a movement she never intended to inspire.

The irony is that while María Sabina’s name remains largely unknown in mainstream culture, she played a foundational role in the psychedelic movement that shaped an entire generation. Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, and other psychonauts became household names, but few people know about the indigenous woman whose ceremonies lit the fuse. She was a healer, a spiritual guide, and a mystic—not an icon of countercultural rebellion. Sabina never sought to be part of any revolution, yet she found herself at the heart of one, all because of the whims of Western curiosity.

One might ask: What does this story reveal about the dynamics between Western modernity and indigenous cultures? Time and time again, we see a pattern of exploitation—the extraction of cultural practices without regard for their deeper meaning, their context, or the people who hold them sacred. In María Sabina’s case, the mushrooms became a symbol of rebellion for a generation disillusioned with the status quo, but for her, they were never meant to serve that purpose. They were sacred tools for healing, not a means for political or social revolution.

As psychedelics see a resurgence in clinical research today, we are witnessing the reclamation of psilocybin mushrooms, not as the drug of choice for acid-dropping hippies, but as potential therapeutic agents for treating depression, anxiety, and PTSD. María Sabina’s legacy lingers in the background of these discussions, ghost-like, a reminder that the roots of this movement aren’t in the sterile labs of Silicon Valley or on the stages of academic conferences but in the hands of a humble Mazatec woman who never sought to start a revolution.

The questions this legacy provokes are complicated and uncomfortable. How often do we, turn sacred, deep traditions into consumer experiences? And, what do we lose when we remove the ritual from the experience? What does it cost the cultures that get swept up in our frenzy for the next mind-altering fix? María Sabina’s story is a stark reminder that the intersection between cultures is never simple, and the repercussions of cultural commodification are often borne by those who can least afford them. Kind of like settlements in legal cases.

Despite the heavy consequences, María Sabina’s spirit endures in the narrative of the psychedelic movement, whether or not her name is widely known. I discovered her in a poster of her in a Hippy joint in Monterrey, Mexico, she was smoking a cigarette and it read something like mother of mushrooms, next to a Bob Marley flag. In many ways, she represents a deeper truth about the nature of psychedelic exploration itself. One that’s a bit harder to comercialise, although I bet you’ll see her here and there on posters and mugs if you pay attention.

Psychedelics, like the mushrooms she used in her ceremonies, have the power to reveal deep truths, to heal, and to transform. But in the wrong hands—or rather, with the wrong intent—they can also become tools of destruction, both for individuals and for cultures.

In her later years, María Sabina continued to hold her veladas, though she expressed that the magic of the mushrooms had been altered. She insisted that the mushrooms were still meant for healing, despite the Western world’s chaotic embrace of them. Her humility and dedication to her practice never wavered, even as the world around her changed beyond recognition. Sabina didn’t need to be a hero of the counterculture. She already had her magic, and her wisdom. It’s just too bad we didn’t listen closely enough to hear her.

Today, there are ongoing efforts to reclaim and honor indigenous knowledge systems, including those of the Mazatec people. Scholars, activists, and descendants are working to ensure that the traditions of people like María Sabina are preserved and respected, rather than exploited for personal or commercial gain. The conversation around psychedelics is shifting again, this time toward a recognition of the importance of cultural context, spiritual integrity, and ethical engagement with these powerful substances.

In this light, María Sabina’s story remains deeply relevant. It serves as both a cautionary tale and a call to action—an opportunity to reframe the way we approach not just psychedelics, but any sacred knowledge from cultures outside our own.

Do a quick google search and you easily find the Life Magazine edition on pdf and you can read the story, its quite fascinating.

As we continue to explore the potential of these substances for healing and growth, we must also reckon with the responsibility that comes with that exploration. We owe it to María Sabina and to all the indigenous peoples whose traditions have been commodified and distorted to do better. To listen more carefully. To respect what we do not fully understand.