On still decorating trees when you've stopped believing in miracles, and why we all secretly miss a bit of magic in this cynical world.

By Rodrigo Garza

Dec 24, 2024

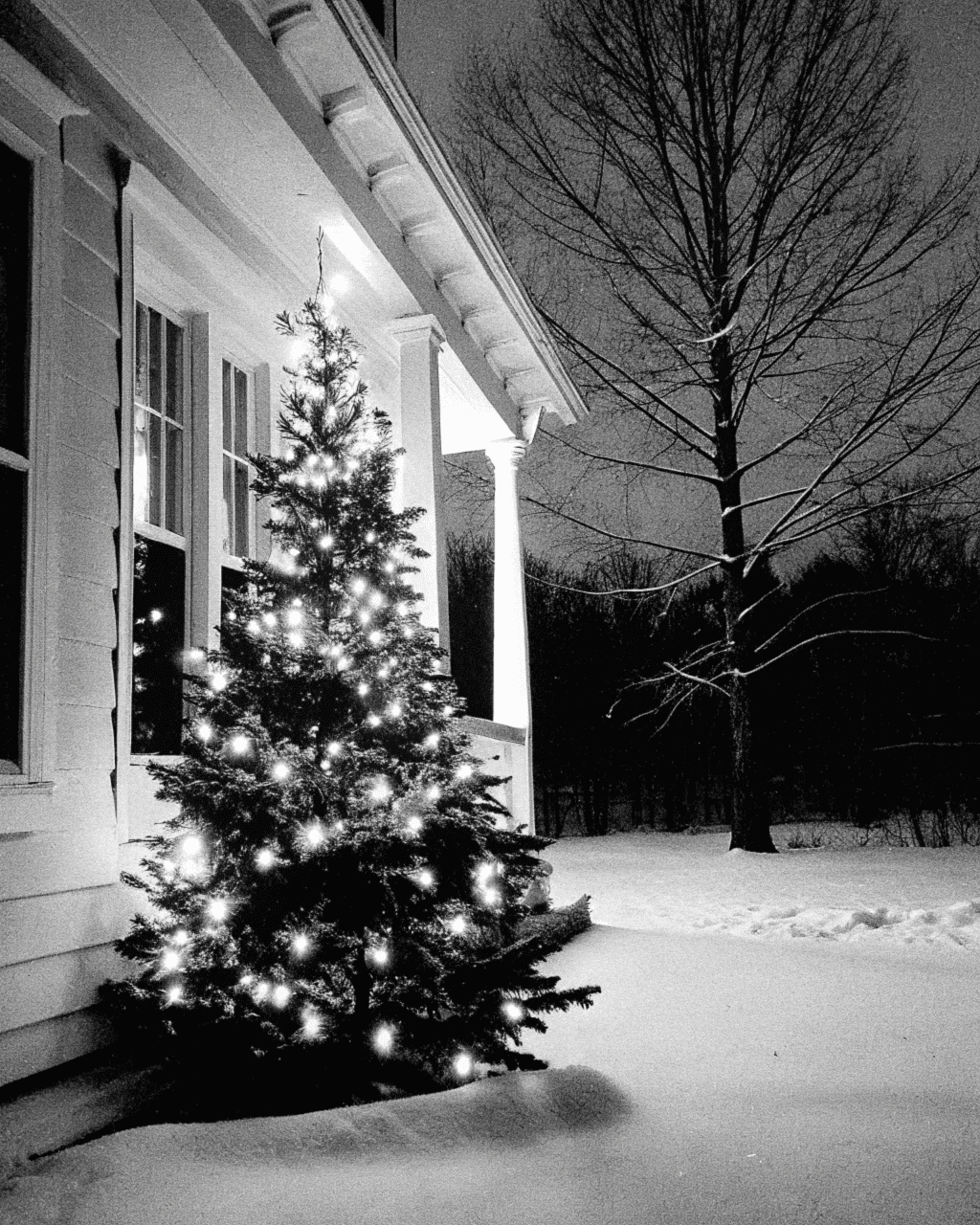

Last week I caught myself humming "Silent Night" while decorating my Christmas tree. here I am, a lifelong atheist, carefully placing ornaments on a pagan symbol appropriated by Christianity, getting ready to celebrate the birth of a messiah I don't believe in. What the fuck is going on?

Growing up in Mexico’s Catholic bubble, I was that insufferable kid who'd corner classmates during recess to explain why God couldn't possibly exist, and how they had the burden of proof. Armed with Richard Dawkins quotes, George Carlin bits, and a teenager's conviction, I thought I was liberating minds. Looking back, I was probably just being an asshole, but I did manage to shake a few faithful foundations. Mission accomplished, right?

Yet here I am, thirty-seven years old, enchanted by Christmas lights, still feeling that inexplicable warmth when "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" plays in some overpriced coffee shop. I've spent years rationalizing my love for this religious holiday. It’s cultural, not spiritual; it's about family; it's just an excuse for good food and gifts. But lately, I'm wondering if I've been missing something deeper.

I’ve noticed how as traditional religion recedes, we've developed an almost religious fervor around other beliefs. Watch how people defend their political ideologies, their dietary choices, their workout routines. Silicon Valley bros talk about AI with the same reverence medieval monks reserved for divine mysteries. Crypto enthusiasts promise salvation through blockchain. Even the contemporary art world has transformed from a space of experimentation into a temple of rigid orthodoxies about representation and identity, we’ve even written a whole article on this.

Nature fucking hates a vacuum, and the void left by Christianity's retreat from Western culture isn't staying empty. We're filling it with a mishmash of wellness influencers, political movements, technological utopianism, and what philosopher John Gray calls "secular religions", belief systems that keep Christianity's promise of progress and redemption while dropping the supernatural elements.

But these substitutes miss a couple of things: Christianity offered a set of beliefs about the universe and also provided a comprehensive framework for understanding human existence, suffering, morality, and meaning. It answered the questions that keep us awake at 3 AM: Why are we here? What happens when we die? How should we live? What the fuck does any of this mean?

The modern replacements feel thin in comparison. Scroll through TikTok "spiritual" content and you'll find a bizarre mashup of commodified Eastern wisdom, positive psychology, and manifestation techniques. It's spirituality as self-help, often stripped of any genuine mystery or depth. We've traded transcendence for "good vibes only."

This spiritual fast food might temporarily satisfy our hunger for meaning, but it lacks the nutritional density of traditional religious thought. Say what you want about Thomas Aquinas or Augustine, but these guys weren't selling five-minute meditation apps. They were wrestling with the fundamental paradoxes of existence.

What I'm realizing – and this would make my younger self fucking fume – is that maybe my militant atheism was itself a kind of fundamentalism. The certainty that there is nothing beyond our material reality requires just as much faith, if not more, as believing in a divine creator. The honest position might be radical uncertainty: embracing the possibility that reality is stranger and more mysterious than our rational minds can grasp.

Look at quantum physics, where particles exist in multiple states simultaneously until observed. Or consciousness, which neuroscience can describe but not explain. Or the fact that mathematics, a human invention, somehow perfectly describes the fundamental laws of the universe. The more we learn about reality, the weirder it gets.

This isn't an argument for returning to traditional religion. That bell can't be unrung. But we need to acknowledge what's been lost in our rush to secularize everything. Christianity provided a shared moral vocabulary, a sense of cosmic meaning, and crucially, a framework for thinking about death that went beyond either denial or despair.

Our current cultural moment feels like a massive exercise in avoiding these fundamental questions. We've constructed an elaborate civilization of distractions, each ping and notification pulling us away from contemplating the mysteries that religions once helped us face. We're more connected than ever, yet increasingly rootless and alone.

The Right wants to force us back to a mythical Christian past, while the Left often seems allergic to any mention of spirituality that isn't immediately qualified with ironic distance. Neither approach adequately addresses our species-wide need for meaning beyond the material.

Maybe what we need isn't a new religion or a militant rejection of all religion, but a new way of engaging with the mysterious. A framework that can hold both scientific rationality and the possibility of transcendence. Something that acknowledges both our need for meaning and the likelihood that any meaning we find will be partially of our own making.

I still don't believe in a personal God keeping score of our sins from heaven. But I'm no longer convinced that the materialist worldview I once defended so vigorously can fully account for the strangeness and beauty of existence. There's something oddly liberating about admitting that.

This Christmas, as I engage in rituals whose original meaning I don't literally believe in, I'm struck by how much wisdom there might be in maintaining connections to traditional practices while remaining open to new understandings. Maybe that's the sweet spot – neither rejecting the past nor being bound by it, but using it as a starting point for exploring the eternal questions every generation must face anew.

So yes, I'm questioning. Not because I've suddenly discovered faith, but because I've lost faith in my own certainty. And in a world increasingly divided between true believers of various stripes, maybe that's not such a bad position to take.